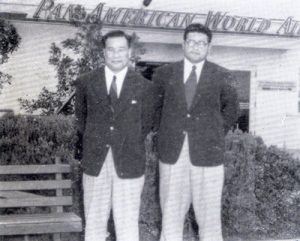

In April 1952 Mas Oyama and Kokichi Endo flew in to Chicago to begin a tour of the American pro-wrestling circuit, and this is really the start of Oyama’s legend as an undefeated fighter who travelled the world facing numerous challengers to test the power of his karate. One account, recycled numerous times on the internet, states that on this American visit he fought and defeated 270 challengers, including boxers and wrestlers; that none of his opponents lasted more than three minutes, and that most of the fights were won by one punch, in just a few seconds.

The circumstances behind the tour are a little obscure. Endo had been a high ranking judoka but had followed the famous Masahiko Kimura into a professional-wrestling career, so from his point of view it was a straightforward pro-wrestling deal. Apparently the well known American wrestler “The Great Togo” wanted to bring Japanese wrestlers to the United States and the name of Endo, who had trained with Rikidozan, Japan’s top pro-wrestler, came up. Mas Oyama’s name also came into the frame somehow, and although he wasn’t a wrestler he was known as a tough guy and an expert in karate. According to Endo, Togo thought that “if he could combine our talents, me and Oyama-kun, he could do good business”, and Endo was clear too that Mas Oyama “only went to America to do his karate demonstrations”,and not to wrestle. Oyama himself said that he was chosen on the personal recommendation of the well known judo teacher Tatsukuma Ushijima. In “What is Karate?” (1958) he wrote that the trip had been organised by the Chicago Pro-Wrestling Association and twenty five years or so after the tour he told “Fighting Arts” magazine that he had been offered $100 dollars a week plus expenses for the trip and in a Japan that was still suffering from the after effects of the Second World war that was a lot of money. “I didn’t want to go really”, he said, “because to me money for budo just didn’t seem right, but I had to live”. And after years of hard training he was in top physical shape too. “Boy, was I strong then!” he recalled.

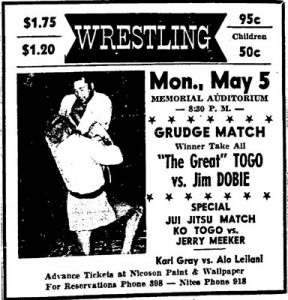

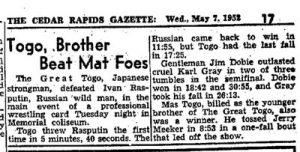

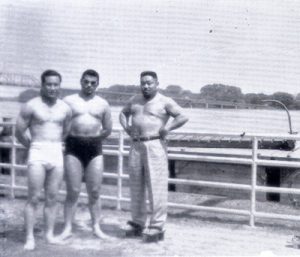

In America Endo and Oyama were teamed up with “The Great Togo”, who was actually Gerald Okamura, a Nisei Japanese. The Great Togo was one of the top heels in wrestling, and Endo and Oyama were to appear as his two brothers, “Ko Togo”, and “Mas Togo”.

In America Endo and Oyama were teamed up with “The Great Togo”, who was actually Gerald Okamura, a Nisei Japanese. The Great Togo was one of the top heels in wrestling, and Endo and Oyama were to appear as his two brothers, “Ko Togo”, and “Mas Togo”.

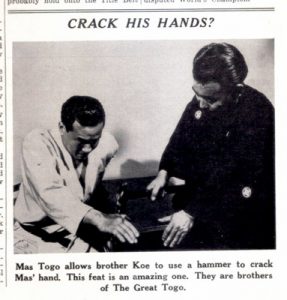

The September 1952 edition of “Ring” magazine included a one page feature on The Great Togo and his two brothers, and it is typical pro-wrestling hype.

“The family with the built in hammers — That’s the Togos. Kazuo Togo, known to his mat followers as The Great Togo, and brothers Mas and Ko, both of whom have recently come over from Japan.

“All are adept with their hands. The Great One needs no introduction — His chop blows have spoken for themselves, but brothers Mas and Ko are new attractions to the mat sport.

“There exists in Japan a singular contact sport known as karatae at which Mas Togo excels. According to is brother Kazuo, Mas went through the normal training period of all Nipponese who go out for a life in karatae.

“The training begins at an early period, in Mas’s case at the age of 14. First the would be karate expert breaks his hand . . . Gentle sport! . . . But it gets better as we check further. The next step is to develop callous skin between the first and second knuckles.

“. . . Having developed the hump of distinction between the digits, he is taught the knack of breaking boards, bricks or anything else lying around that needs adjusting. In the competitive field of karatae many things get adjusted and broken. In fact there are 14 weak points in the human anatomy, one of which is the collarbone. The karatae makes good use of this information. By breaking a collarbone, the victim loses the use of his arms and without his arms his karatae ability is materially lessened.

“The eyes have a habit of popping out of their orbits when the proper spot on the temple is popped . . . Also the lower ribs break easily when one knows how . . . Mas Togo learned all this and more . . .No wonder no one wants to wrestle with him in the U.S.

“The eyes have a habit of popping out of their orbits when the proper spot on the temple is popped . . . Also the lower ribs break easily when one knows how . . . Mas Togo learned all this and more . . .No wonder no one wants to wrestle with him in the U.S.

“. . . One of Mas’s sitting up exercises is to slug his hands with a sledge hammer or other weighty object in order to strengthen his hands.

“The one man wrecking crew served as a special body guard to General McArthur when the home island was first occupied.

“How much training goes into making a karataeman? In the case of Mas it took 14 years. He’s now 28. For three years of that time he spent his life at a temple during which time he was allowed no contact with the outside world. Not even his family was permitted to see him. The course is demanding on the mind as well as the body . . . He was never sure at what moment he might meet someone who could make his eyes pop out.

“Many fall by the wayside in this exacting sport. To do so means a loss of face and to the Nipponese failure, loss of face and disgrace are all rolled into one package. Mas made the grade and should be an interesting addition to American wrestling”.

Mas Oyama was also the subject of a three page feature in the June 1952 edition of “Scene” magazine, in which he was referred to as “Thunderbolt Togo . . . a terrifying exponent of karate — perhaps the deadliest form of weaponless self defense devised by man . . . It cannot be put to full use without maiming or killing. To demonstrate its lethal characteristics against humans is unthinkable.

“The deadliness, nevertheless, is demonstrable. Togo can – and has — killed steers by cracking their skulls with one blow of the fist. He also has ripped out the entrails of dogs with a single slashing stroke of his finger tips . . . The young (28) expert in controlled mayhem is only 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighs, at the most, 180 pounds. He modestly believes that he can handily dispose of ‘maybe 15 or 16’ adversaries in an ordinary free for all.

“The deadliness, nevertheless, is demonstrable. Togo can – and has — killed steers by cracking their skulls with one blow of the fist. He also has ripped out the entrails of dogs with a single slashing stroke of his finger tips . . . The young (28) expert in controlled mayhem is only 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighs, at the most, 180 pounds. He modestly believes that he can handily dispose of ‘maybe 15 or 16’ adversaries in an ordinary free for all.

“‘There are 44 areas of the body that are vital targets’, he says. ‘If I hit a man in any one of those parts he will be crippled, paralyzed or killed.'” The article reported how Oyama allowed a trainer with a two pound hammer to pound his knuckles, “not with all his might, but by no means gently”, and how he said “Harder. You’re only tickling me”. He was described as training every day, doing 300 uninterrupted pushups, rope skipping for forty continuous minutes, doing road work and shadow boxing, and standing on his head for five minutes to strengthen his neck muscles.

“The Great Togo”, Gerald Okamura, and Endo and Oyama, who were to appear as his two brothers, “Ko Togo”, and “Mas Togo”.

After arriving in Los Angeles the Togo brothers travelled almost straightaway to Chicago where Oyama gave his first demonstration at a wrestling show. It was a big crowd and he was a little apprehensive. He began his demonstration with kata, Sanchin first and then Tekki, but the audience soon grew restless and some people began to boo, shouting for the demonstration to be stopped. “I felt dejected, and yet vexed and provoked.“, he remembered. The demonstration moved onto breaking although here he was concerned about the strength of American bricks. He took a brick, but his first shuto strike failed to break it, as did the second. On the third attempt the brick broke in two and the audience was impressed. “As they admired and cheered I gained confidence in myself. I then broke a pile of six pieces of one inch board with seiken, and crushed a stone without difficulty. It seems that these Americans who had seen such a powerful demonstration of karate for the first time were at last giving admiring recognition to this martial art. Thus my first performance proved successful.”

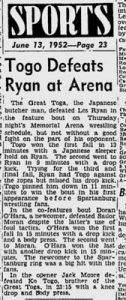

Oyama wrote that his tour with Endo and Togo took them through thirty two states including Iowa, Ohio, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, with Chicago as the centre of operations. They also appeared in Canada.

Oyama wrote that his tour with Endo and Togo took them through thirty two states including Iowa, Ohio, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, with Chicago as the centre of operations. They also appeared in Canada.

In later years, as the Mas Oyama legend grew, this 1952 trip came to be seen as a triumphant tour of America, in which he introduced karate to the West and defeated numerous challenges to prove the power of his technique. In fact it seems to have been an isolated fling with the garish world of pro-wrestling and there is little trace of it all beyond a few scattered magazine and newspaper clippings. In response to my query about all this Robert W. Smith told me that “Oyama’s triumphal tour of the U.S., as far as I was ever able to find out, never happened. And if it had happened, I would have known at the time”. Bob Smith was using little bit of poetic licence there in a letter, as in fact he had sent me a couple of Mas Oyama clippings from that tour; but it was the later exaggeration that he had a problem with. Years later, in his “Martial Musings”, he wrote “I never found one challenger or even one reliable press report”.

Oyama himself, in the early editions of “What is Karate?” wrote that “in a ten month tour we engaged in three matches with pro-wrestlers, gave karate exhibitions thirty times, appeared over television nine times, and had $1,000 dollar prize matches three times”. The reference to the three matches with pro-wrestlers is puzzling: maybe they were the usual worked matches, we don’t know. And the ten months is a little problematical too. Newspaper clippings from July 1952 imply that Oyama was in the USA and Hawaii for four months, and Koichi Endo thought it might have been eight months or so. Then there is a photo of Oyama and his supporters which is said to have been taken on his arrival back in Japan in September 1952, which gives you six months. The whole tour suffers from a lack of documentation.

Three challenge matches quoted by Oyama sounds reasonable, but the exaggeration started very early. In 1953, only months after he had returned to Japan, “Argosy” magazine asked “Is there any defense against karate by an untutored person? If the experience of one karate expert, Oyama, who toured the United States several years ago (sic), is any proof, the answer is no. The small but compact man left more than a hundred of America’s burlier, rougher citizens flat on their backs. One policeman who claimed to be a third ranked judo fighter was carried from the ring with seven broken ribs 90 seconds after the opening buzzer. Fighting a karate expert is for another karate expert only”

The later figure of 270 undefeated challenge matches by way of 270 quick knockouts . . . Presumably this came from the inside cover of Oyama’s “Kyokushin Way” (1979) which states that in his 1952 tour of the U.S. he gave “270 exhibition matches”, which in a nine or ten months tour works out at about one a day. It’s unclear what an exhibition match might be, but somehow this statement became converted into 270 full contact no rules fights to the finish. A figure of 270 though is simply not credible, even in the logistics of arranging such a number of appearances and fitting them into that number of wrestling shows in different towns and cities. And interestingly, the text on that same inside cover goes on to say, just a few lines later, that “He was challenged by two American professional boxers and one professional wrestler and beat them all,” so we are back to three challenge matches again.

In any case the figure of 270 knockouts in 270 fights compares with the all time record of knockouts by a professional boxer, which is held by Archie Moore, who accumulated 145 ko’s over a career which spanned four decades, (1935 to 1963). Sugar Ray Robinson, many people’s pick as the best boxer of all time pound for pound, had 109 ko’s in 209 fights over twenty five years. Even Rocky Marciano, the world heavyweight champion of the early 1950’s, could only reached a knock out percentage of 88%, with 43 ko’s in his 49 fight unbeaten career.

Of course, it could be argued that this was professional boxing where you were facing other professionals, where careers had to be managed over time, and where match-ups had to be arranged and bills put together. But in fact there is a kind of direct comparison with Oyama’s story seventy years before in John L. Sullivan’s great “knocking out” tour throughout America in 1883/84. Sullivan was the first real knock-out artist in boxing and a year after he won the heavyweight title in 1882 he went on an eight month tour throughout the States, giving boxing exhibitions and offering large sums of money to anyone he couldn’t stop in four rounds under Queensberry rules: $250 initially, and eventually $1,000, a sensational amount for those days. In his 1892 autobiography “Reminiscences of a Nineteenth Century Gladiator“, Sullivan wrote that he had knocked out 59 challengers on that tour. An article in “The Police Gazette” of 1905 by one of the members of the touring group gave the number as 39. Frank Moran said it was 36. Michael T Isenberg, in his authoritative “John L’ Sullivan and his Times” tracked The Great John L. through the newspapers of the day and put the number at 11. Adam J. Pollack, in his own excellent book on Sullivan’s boxing career, also gave a detailed account of the tour from local and regional newspapers and identified 12 knock out victims. And the fact that Sullivan’s tour could be traced in detail through the newspapers, and that those papers gave accounts of his challenge matches, demonstrates that it was a genuine national event. So if Mas Oyama had actually knocked out 270 challengers, including, in his own words, “very famous champions”, then he would have been the sensation of the age – but in fact there is hardly any evidence of his tour having taken place beyond a few scattered newspaper and magazine clippings, maybe less than half a dozen, and not one of these contains a ringside account of an Oyama challenge match . . . . Not one.

When, in “What is Karate?” Oyama mentioned having three challenge matches, he gave no details, but accounts could be found elsewhere, for example, in Jay Gluck’s article “Masters of the Bare Handed Kill” which appeared in the March 1957 edition of “True” magazine. This was an influential article as it was later recycled for Gluck’s popular 1962 book “Zen Combat”, which formed the source material for many later writers.

2. The Challenges

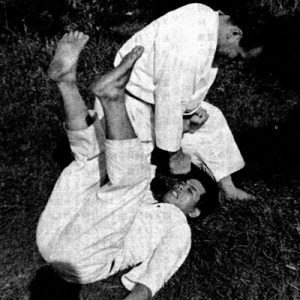

According to Jay Gluck the challenge idea came from Dick Real, “a 6 feet 7 inches pro-grappling champ”, who was offering $1,000 to anyone who could down him. It was in Minneapolis that Oyama accepted the challenge. Real was a difficult opponent and hard to reach, but Oyama feinted with an eye jab, grabbed Real’s hands to pull him in close, and then hit him with three forefist thrusts to the body. “Real went down glassy eyed” after three minutes of fighting.

In Des Moines $1,000 was offered to anyone who could break a brick. A local police officer, who said he was a third dan in judo, tried but his hands started to sweat and even though he hit it till his hands bled he failed to break the brick. When Oyama broke it with one strike the policeman began calling him a fake and challenged him to fight, and Oyama said ok. The officer threw wild roundhouse punches which Oyama evaded before countering with a series of blows to the body which sent the man down with seven broken ribs. The crowd went mad and Oyama had to be escorted out of the building by “a police riot squad”.

In Des Moines $1,000 was offered to anyone who could break a brick. A local police officer, who said he was a third dan in judo, tried but his hands started to sweat and even though he hit it till his hands bled he failed to break the brick. When Oyama broke it with one strike the policeman began calling him a fake and challenged him to fight, and Oyama said ok. The officer threw wild roundhouse punches which Oyama evaded before countering with a series of blows to the body which sent the man down with seven broken ribs. The crowd went mad and Oyama had to be escorted out of the building by “a police riot squad”.

In Chicago Oyama fought Dan Calendar, a tough 250 pound ex wrestler and boxing and judo coach to the police training school. Calendar threw a right hook, Oyama blocked it with his left hand and then leaped in to deliver two knife hand chops with the same hand to Calendar’s neck and temple. “Dan went down, his left hand still cocked to protect him from the right that never came. He was out cold for two hours after only ten seconds in the ring”.

After that there was Becker, a lightweight or middleweight boxer who gave Oyama a lot of trouble with his speed and manoeuverability.. At one point Oyama went out of the ring after missing a punch, but he got back in and eventually took Becker out with a spear hand thrust to the solar plexus. “Becker collapsed, seconds before the bell”.

Of course, Jay Gluck hadn’t seen any of these matches so he may have got the stories direct from Mas Oyama himself, although one possibility is that the source was a 1955 series of articles by Oyama, Shuto Ju Nen”, (Shuto Ten Years) in the newspaper “Toto Shinbun”. These articles were reprinted in “Kakuto K” magazine in its June 2000 and following issues. Here the matches with Dick Real, the wild Des Moines policeman, and George Becker, were described in detail.

Of course, Jay Gluck hadn’t seen any of these matches so he may have got the stories direct from Mas Oyama himself, although one possibility is that the source was a 1955 series of articles by Oyama, Shuto Ju Nen”, (Shuto Ten Years) in the newspaper “Toto Shinbun”. These articles were reprinted in “Kakuto K” magazine in its June 2000 and following issues. Here the matches with Dick Real, the wild Des Moines policeman, and George Becker, were described in detail.

In part 3 of the series of articles Oyama wrote that he was challenged to a $1,000 “shinken shobu” or death match by the 260 pound pro-wrestler Dick Real in Minneapolis. Three minutes into the fight Oyama was able to get in close and jab Real in the eyes. Real covered up and Oyama feinted with his right knee and then launched three forefist blows in to Real’s torso. The big pro-wrestler went down.

The fight with George Becker, a pro wrestler about the same size as Oyama, took place in Charlotte, North Carolina. Oyama described Becker as a handsome man with a lot of female fans who kept yelling at him to “Beat him to death!” and ” Choke him out!” Almost immediately after the match started Becker connected with a punch to the jaw which knocked Oyama out of the ring. Becker just stood and looked down at him but then Oyama noticed a slight loss of concentration and he jumped back into the ring and punched Becker in the back. The two men then got into a clinch and both men went out of the ring. “The audience was going wild. It was no longer just a match, it had turned into a death struggle” The fight continued outside the ring until Oyama dropped Becker with a punch to the body. At that moment he felt a tremendous pain on his back. He instinctively turned and defended against the attack and realised that a woman, who he had now knocked to the floor, had attacked him with a folding chair. The crowd became incensed that he had knocked down a woman and wanted to attack him, but there was a strong police presence and trouble was avoided.

The fight with George Becker, a pro wrestler about the same size as Oyama, took place in Charlotte, North Carolina. Oyama described Becker as a handsome man with a lot of female fans who kept yelling at him to “Beat him to death!” and ” Choke him out!” Almost immediately after the match started Becker connected with a punch to the jaw which knocked Oyama out of the ring. Becker just stood and looked down at him but then Oyama noticed a slight loss of concentration and he jumped back into the ring and punched Becker in the back. The two men then got into a clinch and both men went out of the ring. “The audience was going wild. It was no longer just a match, it had turned into a death struggle” The fight continued outside the ring until Oyama dropped Becker with a punch to the body. At that moment he felt a tremendous pain on his back. He instinctively turned and defended against the attack and realised that a woman, who he had now knocked to the floor, had attacked him with a folding chair. The crowd became incensed that he had knocked down a woman and wanted to attack him, but there was a strong police presence and trouble was avoided.

The story about the police officer in Des Moines who failed to break a brick — or tiles in this version – and then challenged Oyama is told in detail in the series of articles. After failing with the breaking, the officer said “I did not break the tiles, but I can beat you in wrestling.” The article then goes on, (Togo is spelt Tojo throughout the text) : –

“OK. I will do it.” I immediately accepted his challenge. “You’ve got guts”, he smiled and said. “I have to make sure that you have $1000 prize money on the match. Are you sure you’ll give me $1000 if I beat you?” I nodded. He said, “OK. That’s a promise.”

That man was well-known as a strong tough man in his town. Because of that reputation, he could not back down from the challenge, or he would lose face in front of his hometown people. His body was trembling with the excitement and his face showed his determination to beat me to death. The audiences were expressing their excitement in anticipation of the match.

“Go for it! Beat down Mas Tojo!” I heard such screams throughout the arena, then I heard the opening bell. The match began.

The man quickly began throwing his powerful punches. He rushed onto me with his powerful body. The whole audience was like a fire, burning for revenge. I thought, “This fight is not like anything else – He intends to kill me. Either he kills me or I kill him. It is kill or be killed” I made a decision in my mind that I had no choice but to beat him almost to death.

As soon as my mind was made up, I leaned forward, ducking the devastating blows thrown by his enormous arms. Then, almost out of desperation, I unleashed and connected my chudan-zuki; once, twice and three times. Each time my tsuki was connected, I heard the dull un-describable sounds. Seven of his ribs were broken as a result of my chudan-zuki. >He went down for the count with a KO. I won the match in a mere minute and a half. The match was over, but not the crowd. The whole crowd got up on their feet, and began throwing apples and empty bottles like a rain falling on us. They all screamed, “Don’t let Tojo get away. Kill Tojo!” Their screaming of my name all of a sudden became “Tojo!”, “Kill Tojo!” The audience was over-excited. They started rushing toward the ring. I knew there was no way out.

As soon as my mind was made up, I leaned forward, ducking the devastating blows thrown by his enormous arms. Then, almost out of desperation, I unleashed and connected my chudan-zuki; once, twice and three times. Each time my tsuki was connected, I heard the dull un-describable sounds. Seven of his ribs were broken as a result of my chudan-zuki. >He went down for the count with a KO. I won the match in a mere minute and a half. The match was over, but not the crowd. The whole crowd got up on their feet, and began throwing apples and empty bottles like a rain falling on us. They all screamed, “Don’t let Tojo get away. Kill Tojo!” Their screaming of my name all of a sudden became “Tojo!”, “Kill Tojo!” The audience was over-excited. They started rushing toward the ring. I knew there was no way out.

The police, with guns and sticks, began surrounding the ring, trying to protect us. Up to this point, Endo 6-dan was merely my assistant and a helper, but now he came close to me and tried to protect me as well. However, there were just too many people for us to deal with. Making things even worse, the crowd was getting wilder.

I gave up. Or, I better say I had to give up. The crowd turned into a mob screaming out something and moving toward the ring. Even if the policemen, who were surrounding the ring, tried to intimidate the crowd with their guns and sticks, what could that accomplish? It was like going against the raging stream. We were going to be pushed and thrown down by the mob and punished. It was like a death sentence. It was getting close to the unimaginable reality. “There’s no way out, Endo-kun” I said to Endo 6-dan. However, I was remarkably calm, much to my surprise. “Well, there’s no use panicking and trying to get out of this. Like a real man, I will face the crowd.”

Endo-6 dan looked at my face ever so slightly, and stared at the crowd. Death wouldn’t just come to me alone. The angry crowd would definitely harm Endo and kill him as well. I was overwhelmed with the feeling of guilt toward Endo. He got into this because of me.

“There must be a way out, Oyama-kun” Endo-6 dan kept staring at the mob and said it bluntly. He was willing to fight them, fight the angry mob. “OK. I will fight!”. My mind was made up to fight. Just as Endo said, “If they attack us, we must fight back”

“There must be a way out, Oyama-kun” Endo-6 dan kept staring at the mob and said it bluntly. He was willing to fight them, fight the angry mob. “OK. I will fight!”. My mind was made up to fight. Just as Endo said, “If they attack us, we must fight back”

None of this was our fault. I had hurt my opponent by breaking his ribs but he was in the fight with the intention of killing me. It was self defense on my part. If I hadn’t defended myself, and had not fought back, I could have been killed by him.

“There’s absolutely no reason that we deserved to be punished and be killed.”

I stood with Endo shoulder to shoulder. We were ready to fight the mob. “No matter who comes toward us, if they step onto the ring, I will use my long-years-trained shuto, and beat them to death!”

“Kill Tojo!” — “Don’t let him get away alive!”

The crowds were screaming, pushing and shoving at the ring side. The police were overwhelmed. They were still trying to stop the mob. At that brief moment, I heard a very loud siren. It was a sound of an ambulance. Two ambulances arrived. They had come to take my opponent to the hospital. Then, I heard the siren again from the second ambulance. Only one person was hurt, that was my opponent. There were no other injured people here. Endo and I looked at each other and we thought this was a little strange.

I wondered whether one of the ambulances was for me after I was killed. “This is America. They are quick to respond.” I realized later that it was my overreaction to the situation. The second ambulance was there for my rescue. The police who were carrying the stretcher came into the arena, followed by many policemen wearing protective equipment. They fought their way against the angry mob to the ring. The sight of the policemen with equipment appeared to scare the crowd somewhat. The police came up to the ring, surrounded us to protect from the crowd and said, “Step out of the ring. Then leave the arena.” We had no idea where we were going afterwards, but we stepped out of the ring.

Several policemen, with their guns in their hands, were leading us for our escape, breaking up the crowd. With the protection by the police, Endo and I followed them. The whole audience booed and screamed. The shouting voices were showering over us. But, none of them physically touched us after all. I finally got outside of the arena and got on the ambulance. Endo said, almost in a murmur like voice, “Where are they taking us?” “No idea. But we caused the riot. I don’t believe they will let us go free. Most likely, we will be interrogated and put in jail. Well, everything is an experience. I can think of it as a little time off.” However, my expectation was wrong again. The ambulance took us, not to the police station, but in front of our hotel. Noticing the sceptical look on our faces, one of the policemen said, “Please, get off the ambulance and go into the hotel. Then, relax and rest well. You need some rest. (laugh)”. Even before their laughter ended, the ambulance drove off.

Endo and I went back to our hotel room.

“It was a close call.” “We got lucky getting away before their lynching started. It was simply horrible.”

As we were exchanging words like these and we were on the bed, we heard the screaming from downstairs through the window. I heard, “Kill Tojo!” The crowd from the arena had now come to our hotel. On top of that, there were even curious onlookers who had joined them.

“Endo, they came again.” “They never give up. They won’t be satisfied until they kill both of us.”

I thought this time we had no way out. I had thought the trouble was over, but I was wrong. There were more people now than the original crowd at the arena. Some were carrying hunting rifles.

We were resigned to our fate. “No use trying to escape. It’s impossible to get away this time.”

We had to face reality. There was no escape for us. I decided, just as I was in the ring, to meet the mob head on, and to fight to the death.

“Oyama-kun, they came!” said Endo. There was a sound of busy footsteps in the hallway. The mob had arrived. This was our final chapter. Endo and I took our fighting stances in our room. We were ready to fight. Then, several policemen rushed into our room, as if they had kicked through the door. They said, “Get out now, quick! Go to the back door. There is a car waiting for you there. Get in the car and get out of the state.” Although the ambulance left after we were dropped off at the hotel, the police arranged a get-away car parked in the back. “Thank you.” We said it together, and jumped into the hallway. Then, we ran to the back. As the policeman said, there was a car parked there. But there was nobody in the driver seat. I got in, then Endo. Then we heard loud voices. The mob went around the back. I immediately drove off. I heard the sound of a gun firing as we drove away. Then there was more gun fire. Luckily, no bullets hit our car.

I sped through the city, to outside the state. As we were driving through the streets, we saw the lights in the city as though they were totally unaware of this incident. Now, the mob was no longer in our sight. I had managed to escape from the lynch.mob.

Endo said with a smile, “It was really close”. “But” I continued,” it was terrifying racial prejudice. Their resentment against non-whites was simply astonishing. No non-whites should beat whites. There is no reasoning with them, it was just pure hate. But we can’t give up. No matter what they think, if they are tougher and stronger, non-whites can always beat whites”.

3. More on the Challenges

Oyama also talked about the Des Monies fight in an interview with the Japanese “Ooru Yamimono” in July 1953. This seems to be the earliest account he gave of the incident.

“When we went to Iowa”, Oyama explained, “Togo said that in order to get the attention of people we had to create a spectacle. Bricks were brought out and it was announced that $1,000 would be paid to anyone who could break one of these bricks. Then this big guy who looked over thirty came up to the stage. He said he was a state policeman and a third degree black belt in judo. Togo and I were really scared because if this man succeeded not only would the $1,000 be lost but the audience would lose interest in me and Togo would lose his base in Iowa. If you have power you can break one brick but if your striking hand is oily you can’t. You should wash your hands with soap and put a white towel on the brick then it is easier to break. But this guy didn’t know that and his hands were sweaty so he couldn’t break it. Despite the fact that his hand was bleeding he could not break the brick even after several tries. After I broke it on the first try, the officer, not wanting to lose face in front of the crowd, challenged me to a wrestling match and I accepted. The audience was in a frenzy and the guy was deadly serious and looked as if he wanted to kill me. I felt like I’d kill him or he’d kill me. It became an extremely intense match. Now I figured that if I went at him directly without thinking I would lose because I was physically smaller. However, I was really good at poking eyes because I had been practicing it a thousand times a day. When you poke the eyes you really get close to the opponent and put your hand below his nose but you don’t have to put power in the hand. So I did it and he was surprised. Then in the next moment I kicked him in the testicles. He fell down. It took a minute and a half. But in the States it is a foul to kick the opponent there, so the audience got angry. I thought it was ok — After all it was karate. Everyone was yelling ‘We’ll kill you!’ and empty coke bottles showered the stage like rain. Finally I could leave but only by police escort. This was a really bad experience”.

Much later, in another retelling of the tale, “My Karate Journey Round the World” (“Kyokushin Karate” magazine, Vol. 9 No. 1) Oyama actually gave a date for this fight: “The day after I escaped from the Iowa City (April 9, 1952) an article in a local paper said the man I had fought had seven broken ribs and was in a critical condition. Some time later I heard a rumour that he was dead. I have always since hoped that this was not true”.

So the Des Moines policeman keeps appearing in all these accounts, and in fact this match is the only one where there is a reference in the 1952 clippings. A short, unidentified article from one paper refers to “Mild spoken and quiet Masutatsu Oyama of Tokyo . . . who goes under the professional name ‘Mas Togo’ and is also known as ‘Thunderbolt Togo'” and it mentions that he is due to appear on an upcoming TV show hosted by Art Baker called “You Asked For It”. The article also states that “Oyama said that once in Iowa he offered $1,000 to anyone who could beat him in wrestling. A hefty policeman got into the ring and the duel resulted in seven broken ribs for the man in the blue suit. ‘I didn’t mean to get rough but he appeared too serious for my own good’, Oyama humoured”.

At the top of that clipping is a photograph of Oyama breaking a stone and the photo is credited to “Rafu Shimpo”, the Los Angeles based Japanese language newspaper, and “Rafu Shimpo” too had a short article on Mas Oyama in its edition of 18 July 1952. It reads:

“Ever since the victory at the All Japan Championship in the twenty second year of Showa (1947) at Kyoto, 6th dan karateka Masutatsu Oyama has been known to have an undefeated record since the end of the war. Oyama is currently staying with Great Togo on the West Coast after completing a tour of the East Coast, Canada and Cuba. He is scheduled to appear on the TV show ‘You Asked For It’ to demonstrate his karate skills.

“Oyama is a graduate of Takushoku University and a junior of Masahiko Kimura, 7th dan judoka, who came to the United States prior to Oyama’s arrival. Oyama, known here in the States as ‘Mas Togo’ stands 5 feet 8 inches tall and spent approximately thirteen years studying under Gichin Funakoshi.

“During his tour of the East Coast Oyama engaged in $1,000 winner take all challenge matches, defeating all comers within three minutes. When Oyama accepted a challenge from a policeman in Iowa who stood over 6 feet and weighed 250 pounds and was 3rd dan in judo, he reacted to the challenger’s rough tactics and retaliated with a series of chudan zuki, breaking seven of the challenger’s ribs and sending him to the hospital. The fight lasted a mere minute.

“In his up coming TV appearance Oyama is scheduled to demonstrate kata, basic exercises, breaking stones and roofing tiles, and bending a 50 cent coin with two fingers.. Since this will be his first public demonstration of this kind, there is excitement around his appearance.

“Oyama is planning to leave for Hawaii on the 22nd to join Masahiko Kimura, and tour for approximately ten days prior to returning to Japan. Oyama is planning on coming to the States next April for his second tour of the USA”.

For the record, Nei-Chu So, Mas. Oyama’s sensei in Goju ryu, recalled that before Oyama had gone to the USA he had taught him a special eye jabbing technique to use in case he became caught up in a serious fight. On his return to Japan Oyama had told So that he had had to use that technique on a big American who had challenged him. Despite all the various accounts of the Iowa policeman though, it’s curious that the June 1952 edition of “Scene”, which actually mentions the $1,000 challenge offer, refers to an incident in which “At a recent exhibition in Michigan, a powerfully built policeman in the crowd refused to believe what he saw Togo to do to a slab of brick. The sceptical cop accepted a challenge to turn the trick himself. The brick was covered with his blood, but undented when he gave up.” . . . But it doesn’t mention anything about a subsequent fight, and it says Michigan, not Iowa.

The idea of the open challenge had its precedents, going all the way back to the turn of the century when Japanese jujutsu men took on all comers in the music halls. And then in the 1950s, when Judo was really being introduced to the West, Japanese judoka would often have friendly contests with a line up of opponents. To take a random example, “Strength and Health”, October 1955, reported on Japan student champion Watanabe, who threw twenty different opponents in 21 minutes. Watanabe weighed 145 pounds while his opponents went up to 240 pounds. There were many examples like this, but then there was also Masahiko Kimura, the All Japan judo champion, who when he turned professional, seemed to have an open challenge, not just to other judoka, but to anyone. His only condition seemed to be that his opponent wore a judogi.

“Revue Judo Kodokan”, January 1953, had a brief report of Kimura’s 1951 visit to Hawaii: “The gallant challenge that M. Kimura has thrown out to the world has already brought him some surprises . . . in Hawaii, his first exhibition. Kimura (6th dan) is one of the best Japanese champions, who, over the past ten years was Champion of Japan, or one of the finalists. He broke away from the Kodokan (amicably, I believe), and he is offering 1,000 dollars to anyone who is better than him in a judogi. In Hawaii, Kimura’s first opponent came close to him and smashed him in the nose with a magnificent punch, and then immediately jumped out of the ring to hide! The “spiritual pursuit” which then took place amongst the audience lasted eight minutes. When at last Kimura caught his adversary he threw him into the chairs and an atemi knocked him dizzy. Kimura’s second opponent lasted 15 seconds before a shoulder throw left him unable to continue. The United States which is his next stop is preparing to welcome him”.

So maybe the idea of the $1,000 challenge came from Kimura. On the other hand, in the 1953 “Ooru Yamimono” interview it is the Great Togo who thinks up the offer of $1,000 to anyone who can break a brick, whereas in the 1955 series of articles Oyama says the idea of a $1,000 challenge originally came from Dick Real. And this is just one of several inconsistencies in the various different accounts. In the early 1952 newspaper references, the Iowa policeman is hit by a series of chudan zukis which break seven of his ribs, and that is repeated in the Japanese “Toto Shinbun” articles and in Jay Gluck’s account.. Yet in his 1953 interview Oyama himself said that he had jabbed the policeman in the eyes and kicked him in the testicles, meaning incidentally that by western fighting standards he had committed two serious fouls on the man. In the “Toto Shinbun” and Jay Gluck articles it is Dick Real who suffers an eye jab, or an eye jab feint, before being hit by three punches to the body. Jay Gluck refers to Becker as a boxer and states that he was beaten by a spearhand thrust, while Oyama states that Becker was a wrestler and was knocked out by a punch. Gluck says that during that fight Oyama went out of the ring from a slip as he tried to reach Becker while Oyama himself wrote that he was knocked out of the ring by a Becker blow to the jaw. Only Jay Gluck mentions the fight with Dan Calendar.

So maybe the idea of the $1,000 challenge came from Kimura. On the other hand, in the 1953 “Ooru Yamimono” interview it is the Great Togo who thinks up the offer of $1,000 to anyone who can break a brick, whereas in the 1955 series of articles Oyama says the idea of a $1,000 challenge originally came from Dick Real. And this is just one of several inconsistencies in the various different accounts. In the early 1952 newspaper references, the Iowa policeman is hit by a series of chudan zukis which break seven of his ribs, and that is repeated in the Japanese “Toto Shinbun” articles and in Jay Gluck’s account.. Yet in his 1953 interview Oyama himself said that he had jabbed the policeman in the eyes and kicked him in the testicles, meaning incidentally that by western fighting standards he had committed two serious fouls on the man. In the “Toto Shinbun” and Jay Gluck articles it is Dick Real who suffers an eye jab, or an eye jab feint, before being hit by three punches to the body. Jay Gluck refers to Becker as a boxer and states that he was beaten by a spearhand thrust, while Oyama states that Becker was a wrestler and was knocked out by a punch. Gluck says that during that fight Oyama went out of the ring from a slip as he tried to reach Becker while Oyama himself wrote that he was knocked out of the ring by a Becker blow to the jaw. Only Jay Gluck mentions the fight with Dan Calendar.

There was a pro wrestler called George Becker. He died in 1999 at the age of eighty five, and he had wrestled professionally from the 1930s all the way through the 1960s. In fact he and Johnny Weaver won the NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team title in September 1971, when he would have been approaching sixty. George Becker was heavily involved in tag team wrestling from the early 1950s but before that he had wrestled alone, primarily as a light heavyweight. In a 1938 clipping he is referred to as the Champion of the Atlantic Seaboard, and in 1939 he dropped down to middleweight for a bout for the Pacific Coast Middleweight Championship. In that same year in New York he defeated Dave Levin for the World Light Heavyweight title. After the war he held the California State Heavyweight title for a while and then in the early 1950s he settled in Charlotte, North Carolina as a booker for Jim Crockett senior’s Mid Atlantic promotion. From that time he seemed to concentrate on tag team wresting with a number of different partners. He was a well known and popular figure in the North Carolina pro wrestling scene.

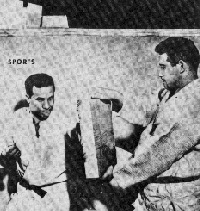

Charlotte, North Carolina, is of course, the place where Mas Oyama said he had his desperate fight with George Becker, and in the early editions of “What is Karate?” there is a photo titled “At Charlotte, North Carolina, with Mr. George Baker”. This is almost certainly George Becker, although he doesn’t look much like Mas Oyama’s description of him, which is that “Becker . . . had a very thick chest, with bear-like hair”. He has his arm round Mas Oyama’s shoulder, and both men are smiling at the camera. Becker, who would have been thirty eight years old at the time, looks ready to go in the ring, but Oyama is dressed in his ordinary street clothes. It’s one of the numerous snapshots taken by Kokichi Endo on the tour, and it doesn’t look anything like a photo of two men who are about to have, or have had, “a death match”. And if you search the internet for George Becker you get a fair number of results, some of which give his title history, but if you search for George Becker and “Togos”, “Great Togo”, “Ko Togo”, “Mas Togo” or “Mas Oyama” you get nothing. Since George Becker turned to tag team wrestling around this time it’s possible he may have had a tag match against the team of The Great Togo and Ko Togo (Kokichi Endo), although no report of such a match is known. There doesn’t appear to be any record at all of a match with Mas Oyama, or “Mas Togo”.

There seems something odd too about Oyama’s account of his fight with “Becker”. He talks about being knocked out of the ring by a punch, and then while Becker suffers a momentary loss of concentration climbing back into the ring and hitting him in the back. The two men then engage in a prolonged struggle as Becker tries to force Oyama down and the crowd go wild. Then they both go out of the ring. They continue fighting outside the ring and then as Oyama finally knocks Becker down he is hit on the back by a woman in the crowd weilding a folding chair. He knocks the woman down by a reflex action and the crowd go crazy when they see that he’s attacked a woman. . . . This doesn’t sound like a real match, no holds barred or otherwise, rather it has all the elements of a worked pro wrestling bout. Oyama would have seen many such matches in his tour of the U.S. pro-wrestling circuit and it’s quite possible that he used all of those elements in the story he wrote later for “Toto Shinbun”. Of course, he may have actually had a worked match with Becker – except that Kokichi Endo, who was there, couldn’t remember Oyama having any matches at all during that American tour.

The identity of the Iowa policeman remains completey unknown. As for Dick Real, he was described as a 6 feet 7 inch, 250 pound pro-wrestling champion, so not the kind of person who would go unnoticed. Originally, when I began to look through all this I assumed I’d be able to find him in the 1950s magazines such as, “Ring”, “Boxing and Wrestling “ and so on – but he wasn’t there. Nor does he seem to appear in the many volumes of J. Michael Kenyon’s “WAWLI (Wrestling As We Liked It) Papers”, or Scott Teal’s “Whatever Happened To?”, a magazine which looks back to the pro-wrestling eras of the 1930s to 1960s. Hisao Maki, a Kyokushinkai insider who apparently had been the ghost writer for Oyama’s “Kenka karate Sekaini Katsu” (“Combat Karate Beats Fighters of the World”), claimed in his own book, “Days with Mas Oyama”, that the story of Oyama’s challenge match with Real was a fiction. Brian Sekiya, who took an interest in the history of Oyama and the Kyokushinkai also searched through professional wrestling sources for Dick Real, without success. In some of the Japanese Mas Oyama books there is a studio photo of a wrestler who is said to be Dick Real, but when Brian checked this photo with Lou Thesz, one of the most famous champions in pro-wrestling history, Thesz said it was actually a photo of Lou “Shoulders” Newman. It seemed that Lou Thesz, who had been in pro-wrestling all his life from the 1930s, had never heard of Dick Real.

There was one actual, quite well known wrestler who appears in the Mas Oyama stories, and that is Tom Rice. It was said that Oyama had beaten Rice towards the end of his 1952 American tour, in San Francisco, Tom Rice had beaten Rikidozan, the famous Japanese pro-wrestler a few months previously when Rikidozan had wrestled in the USA. Rice fought >Rikidozan later twice, in Japan, in 1956, drawing the first match and losing to Riki in the second. He is supposed to have said at the time that he had been beaten a few years before by “the Japanese samurai Mas Oyama” , but there is real doubt about that reference, and the latest thinking on Japanese websites seems to be that it is a fiction, or a fabrication, to enhance Oyama’s reputation. And it’s odd that, although the fight with Rice was said to have been Mas Oyama’s greatest victory, it isn’t included in any of the 1950s accounts by Oyama or others. It only seems to have appeared in the 1970s and again, no one has come up with a contemporary report of such a match. Brian Sekiya also contacted Lou Thesz about Oyama vs. Rice and Thesz’s reply was “I never heard of it, but Tom Rice was a football player and incredible athlete. However, he was not a wrestler or judo or karate person. Where was this guy (Oyama) when we were doing public workouts in Japan and the U.S.?” Apparently the name Mas Oyama meant nothing at all to Lou Thesz.

4. Endo

Kokichi Endo, Mas Oyama’s partner in that tour all those years ago was interviewed for a book “What is Mas Oyama?” (“Oyama Masutatsu Towa Nanika?”), published in 1995, a year or so after Oyama’s death. He was quite diplomatic, and when asked about the Oyama – Rice match; he said he hadn’t seen it, and knew nothing about it, but he had broken up with Togo sometime before Oyama so it could have happened some time after the break up. And that, he told the interviewer, was his usual answer when asked that question. But . . . .“Where was Tom Rice at that time?” he asked. He was in Hawaii, as Hawaiian champion, but Mas Oyama never had any matches in Hawaii as far as he knew. And how could you talk about a Tom Rice match without mentioning Al Karasick, who was the top promoter in Hawaii and had all the rights to Rice at that time? And, he went on “Who let the champion fight?” You had to understand, he explained, that a champion was a prized possession of the promoter: this was the world of professional wrestling and champions didn’t just engage in random challenge matches where outcomes couldn’t be controlled.

When the interviewer then said that “From your tone of voice it sounds to me that you are saying that you never saw Masutatsu Oyama fight anyone in America, not even once”, Endo threw up his hands and responded “Against who?” To the question “Is it possible that even though you never saw Mas Oyama fight wrestlers, you saw Oyama fight a boxer?” Endo’s reply was “I never saw it”

When the interviewer then said that “From your tone of voice it sounds to me that you are saying that you never saw Masutatsu Oyama fight anyone in America, not even once”, Endo threw up his hands and responded “Against who?” To the question “Is it possible that even though you never saw Mas Oyama fight wrestlers, you saw Oyama fight a boxer?” Endo’s reply was “I never saw it”

Endo did remember numerous examples of the crowd getting worked up, but then you had to remember that “The Great Togo” was “the ultimate portrayal of a heel. . . . a real dirty wrestler”, and both he and Oyama were part of Togo’s team. “So it was true that there were times we both staggered back to the hotel, escaping from the fans. But it was not like everything was on Oyama-kun’s shoulders. . . . We encountered many such incidents. For example, our car was surrounded by frantic fans yelling ‘Kill them!’. We decided not to park our car near the arena where our matches took place, because we had no idea what they were going to do with us. So we followed a rule not to stay in a hotel in the same area as the arena” But when the interviewer asked Endo about the story of him and Oyama refusing to do a fixed match, then being kidnapped by gangsters with guns and getting into a streetfight with them – and Oyama knocking out all the gangsters with his karate technique . . . Endo just smiled and said that such stories “made absolutely no sense at all”. They were just stories written to make money, just business. And the stories about Oyama’s 200 wins? — “Imagine how many years it would take to get 200 wins!” he responded.

Endo, in fact, spoke well of Mas Oyama, who he had only known for those few months all those years ago. Throughout the interview he referred to him as “Oyama-kun”, which signified a degree of friendship. Endo thought he might have seen him before that American tour when he did a karate demonstration — pretty much the same demonstration he would give in the States, in fact — at a wrestling show in Yokohama featuring Endo against Masahiko Kimura. Otherwise he didn’t know anything about Oyama before they met, but he did remember that “At that time there were so many lawless areas in Japan. There were stories about a man who was willing to street fight and to do anything, a real tough man. At that time he was in the Ginza district with a certain person . . . . Even though I had just met him Oyama-kun introduced me to this high ranking person in Ginza. He was taking care of Oyama-kun. That person became a very big name later on. Oyama-kun was the kind of person who was clear on distinctions between things. I thought he could trust him”.

The certain person was the Oyabun (boss) of the Ginza. Endo recalled that “There was talk about (Oyama being a Korean) when I went to meet the Oyabun in Ginza. The meeting made me realise that there were things I didn’t understand. I was 25 or 26, still a kid really. I wasn’t mature enough to see things like I do now. Back in the old says the Oyabun never let us spend our own money. So I thanked Oyama-kun for that consideration. He said ‘Don’t worry about it. It was nothing’. I didn’t know quite what to do or how to deal with the kind of life that I witnessed. . . I thought I just met someone from an unknown world. If I describe it as they used to talk in the old days, it was a kind of society or a world where people protect each other with their lives in a real sense. I got to know how they thought at that time”. When the interviewer asked, “Did you feel the yakuza atmosphere?”, Endo replied that he didn’t want to create a misunderstanding, and that Mas Oyama “wasn’t like a cheap gang member or anything like that. He had the moral code, or code of duty of that world. He was a person of jingi, or someone with a moral code in him. I know nothing about his fights or street fights but he was a man of bigger scale than the ordinary gang members, chinpira or gorotsuki”.

Endo felt that Mas Oyama was “a man of conviction”. He would put up with routine or uninteresting things that they might have to do and he never whined or complained. “Even if he felt disinterest underneath he never showed it. His attitude was ‘Let’s do it!’ . . . He was very decisive and made up his mind about things quickly . . . He had a special quality”. He also had great confidence in his karate technique and told Endo “If anything happens I can take care of it with one punch, so don’t worry about anything“. He seemed to have been pretty easy to get along with and Endo didn’t recall any conflict between the two of them.

Endo, who had never seen karate before, thought that Oyama’s karate was “amazing”, and had “great power. . . I can remember to this day”, he said, “the feeling and the audience reaction when he broke three or four boards cleanly with one shot. That had a lot to do with the fact that karate was unknown in America at that time”.

Kokichi Endo was a well known name in the history of Japanese professional wrestling. He was born in 1926 and was a 4th dan judoka before joining Masahiko Kimura’s professional group, the International Judo Association, around 1950. He was an advisor to Rikidozan and in 1954 he won the professional tag team championship as Riki’s partner. He was Rikidozan’s regular tag team partner in fact and “In Showa 31 (1956) their match with the Sharp Brothers brought the whole of Japan to a pitch of excitement”. Even though most of his wrestling was done in Japan, Endo’s name can be found in the WAWLI Papers, for example in the records of Lou Thesz’s 1962 tour of Japan. Endo was around 6 feet tall and as a pro he weighed, he said, around 250 pounds.

After Rikidozan was killed in a night club stabbing Endo became one of the three owners of the Japanese Wrestling Alliance, one of the biggest professional wrestling groups in the world. Interestingly, it seems he was one of the judges at the notorious Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki mixed match in Tokyo in 1976. He was a man, then, who lived most of his adult life in the professional wrestling world. His attitudes were shaped by that, and his only real criticism of Mas Oyama was made from that perspective: “When we talk about beating pro wrestlers and all the exaggerated stories, those are real insults to pro-wrestlers — my honest opinion. As professionals we cannot injure anyone in order to continue our business. Otherwise how can we make a living? There were no promoters who could allow that, especially if you went to America”.

But then to Endo those stories were understandable as business, as promotion, and that too explained why he never said anything about all this when Mas Oyama was alive. “After I left Oyama-kun I had to find a way to live my own life. I had no reason to criticise others who were living different lives. He had his own life to live. . . . I have never seen those matches, you know, all the stories about how he (Oyama) broke a wrestler’s arm, or sent his opponent to the hospital, or such . . . But all those stories created a good business for him, if you look at it that way. It had become a successful product so to speak, so I had no reason to criticise it and ruin the business. I had no reason to do that”.

5. Life and Legend

When I first started looking at all this I wondered if Mas Oyama had ever harboured ideas of becoming a professional wrestler, and whether this early 1952 tour was some kind of tryout for a pro-wrestling career. In fact, it’s clear from Kokichi Endo’s account that Oyama was devoted to his karate and never considered a career in wrestling. His brush with pro wrestling however did seem to influence him in several ways. Kokichi Endo’s inside knowledge was that pro wrestling matches were works (prearranged) and that pro wrestling was a living, a business, whereas Oyama’s stories of his challenge matches played to the assumptions of a large number of Japanese that pro wrestling bouts were actually real. But the early struggles of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, the UFC, demonstrated just how difficult it really was to hold a bare knuckle no holds barred (almost) contest in the USA, or a “shinken-shobu” (death match) as Oyama called it. And as Joseph Svinth pointed out, “As post war professional matches are legally termed exhibitions, the intentional causing of serious injuries is proscribed by law. Therefore mayhem is a possible charge for breaking a policeman’s ribs. At a minimum, workmen’s compensation would have wanted Oyama to pay for the policeman’s time lost at work and medical bills”. Of course if, as Mas Oyama once suggested, his opponent had died after their challenge match, it’s hard to understand how he could have escaped criminal investigation. Joe Svinth also wondered what kind of medical or legal waivers were signed for these contests before anyone entered the ring.

The experience of travelling across America, and his involvement with the pro-wrestling world, must have had some influence on Mas Oyama. At the least it may have given him some ideas of what we now call promotion and marketing. His experience of the USA also made him aware of the potential for the international development of karate, although he recognised that in the future karateka would have to raise their game. In 1956 he told Hiroshi Kinjo that “I would like to see the next generation of Japanese karateka who can compete on the world level and show the world the level of skills and ability of true karateka. In order to achieve such a goal one must have a great deal of dedication and intense hard work. The true karateka must possess power, speed and agility. . . I’m looking forward to seeing such younger generations of karateka”. And he was realistic about the size and physical power of the wrestlers and other athletes he had met in America. At the Oyama dojo a few years later Eiji Yasuda, one of the assistant instructors, mentioned that he wanted to lose 10 pounds or so to get more speed. But, Yasuda remembered, “Oyama sensei didn’t agree with me. He said we had to power up with our training. When I said ‘Sensei, if you put too much muscle on the body you’ll lose speed’, he said ‘You can say that. But when you hit your opponent you should have enough power to knock him over two or three metres. Without that kind of power you wouldn’t be effective in America’ “.

In that 1956 interview with Hiroshi Kinjo, Oyama was quite correct and modest in his answers and when he was asked about his experiences in America he replied “I do not wish to talk about my challenge matches in America. I do not wish to be a hero of some sort. That I believe is an outdated idea . . . For the sake of our students I wish I could eliminate all the stories of fights and challenge matches from the books. When I read books on karate, all they write about are fight stories. Publishers are only thinking about their own financial gain and I believe that is harmful to students”. And although much later in “The Kyokushin Way” (1979) he could write that “I am convinced that, as long as I am permitted to use karate I am unbeatable in unarmed conflict”, and that “When I was in my prime I don’t believe there was a man alive I could not defeat with a single reverse punch“, in the 1958 edition of “What is Karate?” he was much more modest about his victories. “What I experienced during my tour of the States” he wrote, “was that pro-wrestling, boxing and judo are no match for karate. I discovered that my opponents had no preliminary knowledge of karate at all. If they had known the art of attack and defense of karate I might have been defeated since their hands and feet are much longer than mine. In America the wrestlers are mostly giants. My arm is 17 inches round and I am proud of it. On the other hand I am 5 feet 7 inches high and weigh 190 pounds only. But fortunately we karateka have a powerful punch that can knock down any opponent by one stroke. And also we have our own art of kicking that takes our opponent by surprise. If these American wrestlers would learn karate they would be sure to show terrible power. This is true because like other competition, victory or defeat by karate is also dependent largely upon physical strength and speed”.

In that 1956 interview with Hiroshi Kinjo, Oyama was quite correct and modest in his answers and when he was asked about his experiences in America he replied “I do not wish to talk about my challenge matches in America. I do not wish to be a hero of some sort. That I believe is an outdated idea . . . For the sake of our students I wish I could eliminate all the stories of fights and challenge matches from the books. When I read books on karate, all they write about are fight stories. Publishers are only thinking about their own financial gain and I believe that is harmful to students”. And although much later in “The Kyokushin Way” (1979) he could write that “I am convinced that, as long as I am permitted to use karate I am unbeatable in unarmed conflict”, and that “When I was in my prime I don’t believe there was a man alive I could not defeat with a single reverse punch“, in the 1958 edition of “What is Karate?” he was much more modest about his victories. “What I experienced during my tour of the States” he wrote, “was that pro-wrestling, boxing and judo are no match for karate. I discovered that my opponents had no preliminary knowledge of karate at all. If they had known the art of attack and defense of karate I might have been defeated since their hands and feet are much longer than mine. In America the wrestlers are mostly giants. My arm is 17 inches round and I am proud of it. On the other hand I am 5 feet 7 inches high and weigh 190 pounds only. But fortunately we karateka have a powerful punch that can knock down any opponent by one stroke. And also we have our own art of kicking that takes our opponent by surprise. If these American wrestlers would learn karate they would be sure to show terrible power. This is true because like other competition, victory or defeat by karate is also dependent largely upon physical strength and speed”.

In the completely new, 1966, edition of“What is Karate?” (1966) Oyama never referred to his challenge matches in America, nor did he mention them in his other technical books “This is Karate” (1965) or “Advanced Karate” (1970). But then in the early 1970s a great Kyokushinkai promotion exercise began, particularly from Ikki Kajiwara and his brother Hisao Maki and the comic strip “Karate Baka Ichidai”. Then there were the three movies supposedly based on Oyama’s life starring Sonny Chiba, and autobiographical books such as “Tokon” and “Kenka Karate Sekaini Katsu” so “from being a virtually unknown figure to the general public, Mas Oyama became something of a super hero” and the stories of his challenge fights resurfaced, though now in an exaggerated form. . . . and it became ever more difficult to sort out truth from legend. Back in 1998 I spent two days interviewing Jon Bluming who had started training with Oyama in Japan in 1959. Jon had been a favourite pupil, to such an extent that in 1965 he had been graded to 6th dan, making him second only to Oyama himself in the Kyokushinkai organisation. Later the two men drifted apart, but Jon still remembered the Mas Oyama of the old days with affection and respect, and when I asked him about Oyama’s death he choked up and tears came into his eyes.. But one thing he didn’t agree with was the exaggerated stories that started to appear in the 1970s, some of them actually involving him. “The stories just got better and better all the time” Jon said, “and finally, to top it all off, one of his (Oyama’s) students who was a commercial artist, put together a comic book about Oyama, who was with ‘The Animal From Amsterdam’ (Bluming), and man, they really went to the yakuza and knocked them all out and so on. — Unbelievable!”

But then too, many things are just not reported. A few years ago, for example, I tried to establish the fight (boxing) record of Lenny McLean, “The Hardest Man in Britain”. McLean became a well known figure after the publication of his autobiography “The Guv’nor” in 1998. He had a number of fights in the ring yet I found it impossible to get his full record. His one time manager Frank Warren said that McLean had 12 fights, losing 5, though even these figures are uncertain. And the reason for this is that the fights were in “unlicensed boxing”, that is in bouts not recognised by the sports governing body, the British Boxing Board of Control. Because of that they were not reported in the newspapers, and crucially they were ignored by the trade paper “Boxing News”. For the most part they weren’t filmed so for many of McLean’s boxing matches no record seems to exist. For his many fights on club doors and in the street there is simply no record at all.

So just because there are no reports of any Mas Oyama fights in the USA doesn’t mean they didn’t happen, but it does make verification impossible, and that, and the testimony of Kokichi Endo, raises major doubts. When Oyama wrote that his opponents were “famous heavyweight boxers”, it is reasonable to ask exactly who they were. We should be able to pick their names out of the heavyweight ratings which appeared month after month in magazines such as “The Ring” and “Boxing and Wrestling” – but we can’t. The supposed record of 270 victories in the ring is simply not credible, although to be fair, it doesn’t seem that Oyama himself ever made that claim.

Those stories were an important part of the promotion and expansion of Kyokushinkai and they did inspire many of Oyama’s followers . . . but Kyokushinkai is a strong enough style now to stand up on its own terms. This was all a long time ago and I don’t suppose it matters now, except for purposes of historical accuracy.

6. Tameshiwari

After he returned to Japan after his 1952 tour, America must have remained in Mas Oyama’s mind because he returned there several times. There are references for example to visits in 1954 and 1960, but we don’t seem to have any documentation on these trips. During his 1962 stay he gave a demonstration at the North American Karate Championships at Madison Square garden. “Black Belt” reported that “The 8th degree Black belt of Kyokushinkai karate gave an impressive demonstration, crushing granite rocks, snapping bricks and boards with his bare hands. As black belt Frank Fanzone made repeated lunges at him with a butcher’s knife Master Oyama twisted, blocked and chopped with many combinations showing how deadly his art could be in practice.” This event was also covered by the New York Times which called him “the toughest man in the world”. When Oyama returned in 1965 he again did a demonstration at the North American Tournament in New York. “Black Belt” was there again, reporting that “A highlight of the June tournament was the demonstration by Mas Oyama, who performed tensho kata (breathing and tension movements), broke planks and bricks, and startled all by cleaving the necks of two bottles that remained in place”.

After he returned to Japan after his 1952 tour, America must have remained in Mas Oyama’s mind because he returned there several times. There are references for example to visits in 1954 and 1960, but we don’t seem to have any documentation on these trips. During his 1962 stay he gave a demonstration at the North American Karate Championships at Madison Square garden. “Black Belt” reported that “The 8th degree Black belt of Kyokushinkai karate gave an impressive demonstration, crushing granite rocks, snapping bricks and boards with his bare hands. As black belt Frank Fanzone made repeated lunges at him with a butcher’s knife Master Oyama twisted, blocked and chopped with many combinations showing how deadly his art could be in practice.” This event was also covered by the New York Times which called him “the toughest man in the world”. When Oyama returned in 1965 he again did a demonstration at the North American Tournament in New York. “Black Belt” was there again, reporting that “A highlight of the June tournament was the demonstration by Mas Oyama, who performed tensho kata (breathing and tension movements), broke planks and bricks, and startled all by cleaving the necks of two bottles that remained in place”.

During one of those New York visits, Joe Lopez, who was a Peter Urban student at the time, went to see Oyama taking a training session at Augustin de Mello’s karate school in Greenwhich Village. The lesson was mainly basics, powerfully done: Mas Oyama’s forefist thrust, Joe thought, “was like a piston”. Joe was also a participant at the Madison Square Garden tournament and he remembered Oyama going through two bricks with a shuto strike and then breaking another brick with a punch: his assistant held the top half of a brick in both hands and then Oyama hit it with his forefist, knocking the bottom half away while the other half remained in the assistant’s hands. When Joe went back into the changing rooms some karateka were there and they were trying to break some bricks left over from Oyama’s demonstration, and they couldn’t do it. After several tries Joe was able to break one of the bricks, but he remembered that these were genuinely hard bricks: they weren’t easy to break, and yet Mas Oyama was just punching right through them. That experience gave him a real respect for Oyama’s physical power.

“Strength and Health”, May 1954, in its column “Strongmen the World Over” had the following “‘Hard as nails’ would be a rather mild description of the fantastic punching power of the Japanese karate experts. Karate is truly a mayhem form of judo featuring violent blows. Smashing a 2 inch plank with a single blow of the bare fist is a routine stunt for a karate expert. In an exhibition performance in this country last year, one of the Japanese masters of this form of combat split a pile of five one inch boards with a blow delivered by his rock-like fist”. Although he wasn’t named, this was obviously a reference to Mas Oyama, so his 1952 visit did make an impression. Yet oddly, it seemed to pass over the head of much of the martial arts community — the judo community as it was then. Presumably this was because it was part of a wrestling promotion and was restricted to the professional wrestling circuit.

When karate was first introduced to the West one of its main attractions was breaking and instructors were invariably asked to demonstrate it. It was something that just used to fascinate people, and so in the early 1950s Mas Oyama’s breaking feats must have seemed amazing to the American public. According to Oyama, writing in 1965, “After a while in America our hands earned the name ‘the hands of a god.'” This seems to be the origin of the grandiose 1970s name for Oyama of “God Hand”. That term, however, doesn’t appear in any of the American newspaper and magazine clippings of the time.

He had been conscious of the effect that breaking had on people and he had worked hard on the techniques. In “This is Karate” he wrote: “After we had devised our own breaking methods we showed them to a very famous Chinese kempo master, who was awe-struck with admiration”. Oyama must have had some unusual training methods too because he also stated that “We were the first to break dogs’ necks with the knife hand and to rip the horns from some forty cows.” He wrote that people who could actually break three bricks with the knife hand were entitled to the name “master of the knife hand”, adding that “Anyone who can break more than two bricks with the knife hand could probably use the same technique to break the neck of a large dog. He could also rip the horn from a cow. Our own experience has taught us that it is possible to break a Japanese dog’s neck with one knife hand blow. We have actually done this many times, thought that was some years ago. The same is true of ripping the cow’s horn”.

Oyama had torn the horns of cattle and broken dogs’ necks but could he break more than two bricks? Oddly, there do not appear to be any photos of him doing so. In “What is Karate?” (1958) he simply wrote that he could “break two red bricks at a time if my condition will permit.” When Robert W Smith reviewed the new edition of “What is Karate?” in 1966 he pointed out that the well known Hung I-Hsiang of Taiwan could break three supported bricks (that is, resting between two supports), or two unsupported bricks: that is, bricks lying on a flat surface, which is obviously much more difficult. Hung did the breaks with a hammer fist. Typically, John Keehan, or “Count Dante” claimed to be the only man alive who could break two bricks lying flat. Steve Morris, the British martial artist, saw Robert W. Smith’s book “Chinese Master and Methods”, in which Hung’s feats were described, and he resolved to duplicate them. There is footage of Steve on the internet breaking two bricks unsupported with a hammer fist and three with an elbow. He is also shown in the British magazine “Combat” (1976) breaking three bricks unsupported with a palm strike. Frank Perry, a one time Kyokushinkai student of Steve Arneil would break three bricks with a knife hand in demonstrations. A lot of Korean Taekwondo instructors were good at breaking too, as were some the Chinese “hard chi-kung” practitioners. I haven’t looked into this in any detail, but there were probably quite a few people who could duplicate or better Oyama’s published brick breaking feats.

Of course, bricks and boards vary in strength so actually it’s difficult to make comparisons or judgements. Kokichi Endo recalled that Oyama could always break four or five boards in Japan but in the USA sometimes he could manage only one or two. He quickly learned which boards were the best for breaking and when he could he would buy up a supply and load them into the car they used to travel in. In “This is Karate” Oyama wrote that “When we were in Mexico we attempted to break three boards — each one inch thick — of a type of wood different from that to which we were accustomed. This wood was as hard as iron and had a grain so close that you could not even see it. Even one board would have been difficult to break, let alone three. At last we succeeded in breaking one, but the whole incident was a grim error.” Mexico can’t have been a wholly happy experience for him because a few pages later in the same book he also wrote that “We personally made a big mistake in Mexico twelve years ago by choosing the wrong type of brick”, adding the advice to “Avoid the types of bricks the Americans sometimes pave streets with, because they are as hard as iron and impossible to break with the bare hands”.

Breaking objects with the hands and feet has probably existed in the eastern martial arts for hundreds of years. In Japan it certainly predated the introduction of karate in the 1920s. William Bankier, the strongman “Apollo”, wrote about the edge of the hand blow in his 1905 book “Jiu-Jitsu. What It Really Is”, adding that “Some of the Japs who made a study of this sort of thing have been known to actually break very large stones with their bare hand. To such an extent had these men developed the heel or side part of the hand that it almost became as hard as stone.” During his military service in France in World War 1, Bob Hoffman, the founder of “Strength and Health” magazine saw an example of breaking in Paris, of all places: “In France during the war, Bob Hoffman told me that he saw a Japanese sidewalk performer actually break slabs of marble with chop blows of his hand. The side of his hand was about half an inch thicker than a normal hand”. In 1940 the “Japanese American Courier” reported that “Marking its 34th anniversary the Tacoma (judo) dojo will hold its annual tournament Sunday afternoon at the Buddhist Church auditorium . . . Over 40 black belts are listed for action. An additional feature on the programme will be Masato Tamura’s ‘rock breaking’ demonstration via the ancient Japanese art of “kiai jutsu”. He will also oppose a quintet of picked black belts”. Tamura was a well known judoka who had got his third dan during Jigoro Kano’s visit to America in 1938. In none of these accounts, incidentally, is there any mention of karate.