The word Kata means “shape” or “form”. The kanji for Kata 型 is composed of the following characters:

形 Katachi meaning “Shape”

刈 Kai meaning “Cut”

土 Tsuchi meaning “Earth” or “Soil”

Literally translated, kata means “shape which cuts the ground”.

The Kata as we know and practice in Kyokushin Karate trace their origin back to the island of Okinawa. Okinawa is one of a chain of islands that are collectively known as the Ryukyu Islands. Okinawa lies 885km (550 miles) east of mainland China, approximately halfway between China and Japan.

The history of this is long and complicated, so I will try to abbreviate as much as possible. If you would like the complete history there are many sources available. I will probably be adding or editing to this article over time.

History

During the 11th century, many Japanese warriors fled Japan, because of the Taira-Minamoto wars, and made their way to Okinawa. The bujitsu of the Minamoto samurai had a large influence upon the fighting methods employed by the Okinawan nobles.

During the 11th century, many Japanese warriors fled Japan, because of the Taira-Minamoto wars, and made their way to Okinawa. The bujitsu of the Minamoto samurai had a large influence upon the fighting methods employed by the Okinawan nobles.

In 1377 the King of Okinawa formed an allegiance with the Chinese and a relationship between the two countries flourished, causing migration and cultural exchange between the two. The towns of Shuri in the north and Naha in the south were well known trading centres. One of the things brought back to Okinawa was fighting styles picked up during these trips. Originally called China Hand or T’ang Hand (唐手). “China Hand” had a large influence in the development of Okinawa Tōde, the Okinawan fighting system. This gave rise to two major styles from each area respectively. Shuri-te and Naha-te. “Te” meaning hand.

In 1477 the King of Okinawa imposed a ban on the use and ownership of weapons. They were confiscated and the Okinawan Nobles were ordered to live near Shuri. This only heightened the training in Tōde. Then, in the 1600’s, the Japanese ordered the Satsuma clan to invade Okinawa. The Samurai prohibited the use of weapons and eradicated the practise of their local fighting arts.

The Okinawans began training in secret with family and a few trusted students. During this time their empty hand developed and they practiced in the use of fighting with farming and fishing tools, which gave rise to the development of Kobudo.

It is also important to understand that the Okinawan fighting systems were closely guarded secrets. Therefore their Kata and its application, or bunkai, became secretive. By affording movement, multiple applications and great amounts of information could be contained in a kata of a manageable length. Deadly techniques were hidden in the Kata movements, which were only understood by a select few. The practise of Tōde went completly “underground” hidden from the Japanese oppressors of that time. They practised in small groups, or one-on-one with their teacher, and this was how the Ryu (school) was passed down. There were no written records or books, so techniques were passed along in Kata, making it difficult therefore to trace their true origin.

Many of the kata practised at this time were Chinese in origin, but they would have been influenced by the techniques and concepts collected from fighting traditions originating from other parts, like the Samurai of Japan. The Okinawans also developed their own kata to record their fighting systems. The only purpose behind a kata at this point in history was to record, like a living encyclopaedia, highly effective and brutal methods of combat, and to provide a training method to help perfect those methods.

In 1868, Japan went from feudalistic society to democracy. During this time the Japanese abandoned many of the aspects of the Okinawan culture that were attached to feudalism. The class structure, the wearing of swords by samurai, the styling of the hair in to the “top-knot” etc., were all abolished.

In 1891, during their medical for recruitment into the army, the exceptional physical condition of some karate exponents was noted. As a result, the military enquired as to whether karate could be of use to the Japanese army, as Jujitsu and Kenjitsu had been. This was abandoned due to the disorder of the karate community, the length of time it took to become competent and due to fears that the Japanese troops may use the new found skills in brawls.

Shuri-te

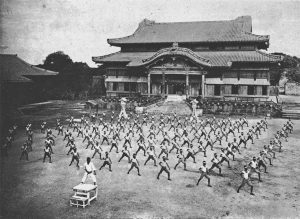

At the turn of the twentieth century a group of karate practitioners campaigned to get karate placed onto the Okinawan school system’s curriculum in the belief that karate practise would promote healthy bodies, improve character and would result in students who were more productive in Japanese society.

In 1901, Anko Itosu, a teacher and practionor of Shuri-te (Northern styles of Karate) campaigned successfully to get karate onto the physical education program of an Okinawan elementary school. As it stood, Itosu believed karate to be too dangerous to be taught to children and set about disguising the more dangerous techniques. As a result of these modifications, the children were taught the kata as mostly blocking and punching. It is also said that Itosu also changed many of the more dangerous strikes (taisho, nukite etc.) into punches with the clenched fist. This enabled the children to gain such benefits as improved health and discipline from their karate practice, without giving them knowledge of the highly effective and dangerous fighting techniques that the kata contain.

Itosu was eventually appointed as karate teacher to an Okinawan college, and a few years later he wrote a letter to the education department that outlined his views on karate. In this letter, he asked that karate be introduced into the curriculum of all Okinawan schools. Itosu was granted his wish and karate became part of the education of all Okinawan children.

Itosu’s modifications resulted in huge changes in the way the art was taught. The emphasis was now placed firmly upon the development of physical fitness through the group practice of kat

a. The children would receive no instruction in the combative applications associated with the kata and deliberately misleading labels were adopted for the various techniques. Today, it is Itosu’s terminology that is most commonly used throughout the world and it is important to understand why this terminology developed.

When studying the combative applications of the kata, you must remember that many of the names given to the various movements have no link with the movement’s fighting application. Terms such as “Rising-block” or “Outer-block” stem from the watered down karate taught to Okinawan school children, not the highly potent fighting art taught to the adults. When studying bunkai be sure that the label does not mislead you. Itosu’s changes also resulted in the teaching of kata without its applications. The traditional practice had been to learn the kata, and then when it was of a

sufficient standard (and the student had gained the master’s trust) the applications would then be taught alongside the kata. However, it now became the norm to teach the kata for its own sake and the applications may never be taught (as is sadly still the case in the majority of karate schools today).

The majority of today’s karate practitioners practice the art in the “children’s way” and not as the effective combat art it was originally intended to be. Indeed Itosu himself encouraged us to be aware of this difference. Itosu once wrote, “You must decide whether your kata is for health or for its practical use.”

In the early 1900’s Gichin Funakoshi, his student, enhanced the popularity of Karate by demonstrating his art in front of the Emperor of Japan. He spent the rest of his life in Japan teaching his system, his students called Shotokan, until his death in 1957. Because of the poor relationship Japan had with China, he was instrumental in changing the kanji for Karate from China Hand (唐手) to Empty Hand (空手), thus removing the reference to China.

Naha-te

The Kata coming out of the South of Okinawa were very different than it’s cousin to the North. Naha-te was primarily based on the Fujian White Crane systems of Southern China, which trickled into Okinawa in the early 19th century through Kumemura (Kuninda), the Chinese suburb of Naha, and continued developing and evolving until being finally formalized by Higaonna Kanryō in the 1880s.

Mar 10, 1853 – Oct 1915

Credited for the early development of Naha-Te is Kanryo Higaonna (1853-1915). Kanryo Higaonna students include Chojun Miyagi (1888-1953), the founder of Goju-ryu. He became a disciple of Kanryo Higaonna, when he was 14. He endured harsh ascetic practices and in 1915 went to Fujian Province in China to perfect his skills in the martial arts. He also undertook a lot of

Apr 25, 1888—Oct 8, 1953

research on noted Chinese warriors. As a result, he was able to take over and organize karate techniques and the principles of the martial arts that he had been taught. He consolidated modern karate do, incorporating effective elements of both athletics and the martial arts in addition t

o the principles of reason and science.

The traditional Kata passed down from Kanryo Higaonna to the present include: Sanchin, Saifa, Seienchin, Shisochin, Sanseiru, Seipai, Kururunfa, Seisan, and Suparinpei (or Pecchurin).

In addition to such traditional Kata, Goju-ryu has added Kokumin Fukyugata, a series of Kata created by Chojun Miyagi for the nationwide popularization of the school Gekisai I, Gekisai II and Tensho-which complete the Kata of Goju-ryu for Tanren.

Unlike their cousins to the north, the kata of Naha-te did not get incorporated into the school system and thus retained their original purpose, of passing along effective self-defense and combat applications. This difference is quite noticeable when viewing both styles, particularly in any demonstration of the application, or bunkai. Styles from Naha-te, like Goju-ryu and Uechi-ryu can be very brutal in their training practices and application.

Kyokushin Kata

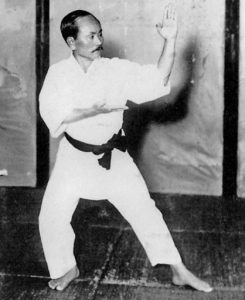

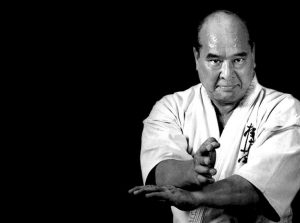

Sosai Masutatsu (Mas) Oyama

The founder of Kyokushin, Masutatsu ‘Mas’ Oyama was skilled in both major styles born from the two areas of Okinawa. Shotokan (Shuri-te), which he was a 4th Dan Black Belt under Funakoshi, and Goju-ryu (Naha-te), which he obtained a 7th Dan Black Belt under Gogen Yamaguchi.

Mas Oyama, when creating his own stye, incorporated kata from both of the traditions. Hence why the large number of kata found in Kyokushin.

This is a little ironic in itself, as Kyokushin is most famously known for its fighting, not for it’s kata and applications.

IFK Canada Representative

Mas Oyama also emphasized the three fundamental principles of kata:

技の緩急 Waza no Kankyū The Relative Tempo of Techniques: The tempo of the kata varies – some techniques are performed quickly, while others are done more slowly.

力の強弱 Chikara no Kyōjaku The Relative Force of Power: The power of a technique derives from the proper balance between strength and relaxation.

息の調整 Iki no Chōsei The Control of Breathing: The correct timing (inhaling and exhaling) and force of the breaths (Kiai 気合, Ibuki 息吹 or Nogare 逃れ) are essential for proper techniques.

Through the practice of kata, the traditional techniques used for fighting are learned. Balance, coordination, breathing and concentration are also developed. Done properly, kata are an excellent physical exercise and a very effective form of total mind and body conditioning. Kata embodies the idea of Renma 錬磨, or “polishing” – with diligent practice, the moves of the kata become further refined and perfected. The attention to detail that is necessary to perfect a kata cultivates self discipline.

Through concentration, dedication and practice, a higher level of learning may be achieved, where the kata is so ingrained in the subconscious mind that no conscious attention is needed. This is what the Zen masters call Mushin 無心, or “no mind.” The conscious, rational thought practice is not used at all – what was once memorized is now spontaneous.

Through concentration, dedication and practice, a higher level of learning may be achieved, where the kata is so ingrained in the subconscious mind that no conscious attention is needed. This is what the Zen masters call Mushin 無心, or “no mind.” The conscious, rational thought practice is not used at all – what was once memorized is now spontaneous.

Mas Oyama said that one should “think of karate as a language – the Kihon 基本 (basics) can be thought of as the letters of the alphabet, the Kata 型 (forms) will be the equivalent of words and sentences, and the Kumite 組手 (fighting) will be analogous to conversations.” He believed that it was better to master just one kata than to only half-learn many.

The practice of traditional kata is also a way for the karateka to pay respect to the origins and history of Kyokushin Karate and the martial arts in general.

Kata list by historical area

According to a highly regarded Kyokushin text, “The Budo Karate of Mas Oyama, by Cameron Quinn, long time interpreter to Mas Oyama, the kata of Kyokushin are classified into Northern and Southern Okinawa Kata.

Northern

The northern kata stems from the Shuri-te tradition of karate, and are drawn from Shotokan karate which Oyama learned while training under Gichin Funakoshi. Some areas now phase out the prefix “sono” in the kata names.

- Taikyoku Sono ichi

- Taikyoku Sono Ni

- Taikyoku Sono San

The Taikyoku kata were originally created by Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan karate.

- Pinan Sono Ichi

- Pinan Sono Ni

- Pinan Sono San

- Pinan Sono Yon

- Pinan Sono Go

The 5 Pinan katas, known in some other styles as Heian, were originally created in 1904 by Ankō Itosu, a master of Shuri-te and Shorin ryu (a combination of the shuri-te and tomari-te traditions of karate). He was a teacher to Gichin Funakoshi. Pinan (pronounced /pin-ann/) literally translates as “Safe From Harm”. For a full history of these kata click here.

.

Some organizations have removed the “Dai” from the name, calling it only “Kanku”, as there is no “Sho” or other alternate Kanku variation practiced in kyokushin. The Kanku kata was originally known as Kusanku or Kushanku, and is believed to have either been taught by, or inspired by, a Chinese martialartist who was sent to Okinawa as an ambassador in the Ryukyu Kingdom during the 16th century. Kanku translates to “sky watching”.

The Kata Sushiho is a greatly modified version of the old Okinawian kata that in Shotokan is known as Gojushiho, and in some other styles as Useishi. The name means “54 steps”, referring to a symbolic number in Buddhism.

A very old Okinawan kata of unknown origin, the name Bassai or Passai translates to “to storm a castle”. It was originally removed from the kyokushin syllabus in the late 1950s, but was reintroduced into some kyokushin factions after Oyama’s death and the resulting fractioning of the organization.

This kata is a very old Okinawan kata, also known as Tekki in Shotokan. It is generally classified as belonging to the Tomari-te traditions. The name Tekki translates to “iron horse” but the meaning of the name Naihanchi is “internal divided conflict”. It was originally removed from the kyokushin syllabus in the late 1950s, but was reintroduced into some kyokushin factions after Oyama’s death and the resulting fractioning of the organization.

Unique

These three kata were created by Mas Oyama to further develop kicking skills and follow the same embu-sen (performance line) as the original Taikyoku kata. Sokugi literally means Kicking, while Taikyoku translates as Grand Ultimate View. They were not formally introduced into the Kyokushin syllabus until after the death of Oyama.

Southern

The southern kata stems from the Naha-te tradition of karate, and are drawn from Goju-ryu karate, which Oyama learned while training under So Nei Chu and Gogen Yamaguchi. One exception may be the kata “Yantsu” which possibly originates with Motobu-ha Shito-ryu, where it is called “Hansan” or “Ansan” – there is much debate about the origin of Yantsu.

- Gekisai Dai

- Gekisai Sho

Gekisai was created by Chojun Miyagi, founder of Goju-ryu karate. The name means “attack and smash”

- Tensho

Tensho is one of the older, more fundamental katas. Its origins are based on the point and circle principles of Kempo. It was heavily influenced by the late by Chojun Miyagi and was regarded as an internal yet advanced Kata by Oyama. The name means “rotating palms” and is regarded as the connection between the old and modern Karate.

Sanchin is a very old kata with roots in China. The name translates to “three points” or “three battles”. The version done in kyokushin is most closely related to the version Kanryo Higashionna (or Higaonna), teacher of Chojun Miyagi, taught (and not to the modified version taught by Chojun Miyagi himself). For a full history of this important kata, click here.

- Saifa (Saiha)

Originally a Chinese kata. It was brought to Okinawa by Kanryo Higashionna. Its name translates to “smash and tear down”.

- Seienchin

Originally a Chinese kata, regarded as very old. It was also brought to Okinawa by Kanryo Higashionna. The name translates roughly to “grip and pull into battle”.

- Seipai

Originally a Chinese kata. It was also brought to Okinawa by Kanryo Higashionna. The name translates to the number 18, which is significant in Buddhism.

Yantsu originates with Motobu-ha Shito-ryu, the name translates to “keep pure”

- Tsuki no kata

This kata was created by Seigo Tada, founder of the Seigokan branch of Goju-ryu. In Seigokan goju-ryu the kata is known as Kihon Tsuki no kata and is one of two Katas created by the founder. How the kata was introduced into Kyokushin is largely unknown, but since Tadashi Nakamura are often claimed in error as the creator of the kata in Kyokushin, speculations are that he introduced it into Kyokushin after learning it from his Goju-ryu background.

Unique

- Garyu

The kata Garyu, is not taken from traditional Okinawan karate but was created by Oyama and named after his pen name (Garyu =reclining dragon), which is the Japanese pronunciation of the characters 臥龍, the name of the village (Il Loong) in Korea where he was born.

Ura Kata

Several kata are also done in “ura“, which essentially means all turns are done spinning around. The URA, or ‘reverse’ kata were developed by Oyama as an aid to developing balance and skill in circular techniques against multiple opponents.

- Taikyoku sono ichi ura

- Taikyoku sono ni ura

- Taikyoku sono san ura

- Pinan sono ichi ura

- Pinan sono ni ura

- Pinan sono san ura

- Pinan sono yon ura

- Pinan sono go ura

To view the Kata of Kyokushin, click here.

As you can see, the history of the Kata in Kyokushin Karate is vast, and this article barely scrapes the surface. If you are interested, I strongly urge you to do your own research. Perhaps even beginning with a favourite kata of your own to perform. Research it, not just historically, but also from the aspect of bunkai, to truly understand the “secrets” that lay within.

Hi folks, Having come back to Kyokushin after 30 years or so I am re-learning some of the Kata mostly with no changes to they way I have originally learned them. Working on Kanku (Dai) and I am surprised that there seems to be 2 variations now! Regardless of stances etc, one major difference is in the part that you do the mae geri & uraken+yoku geri that in one version is done to one direction only but in the other version is done in two directions. Is this an IKO1 and IKO2 thing or it has always been like… Read more »

Another fantastic article Scott! Thanks so much for sharing. With so many dojos moving away from kata and focusing on kumite, it’s encouraging to find this information. Particularly for guys like me who are a bit older and have only recently discovered Kyokushin. It’s a fascinating topic and you’ve presented an enormous amount of info in a very concise, enjoyable manner. Osu!

Ura isn’t Kata developed by SOSAI. “Tha” is Ashihara. In 1975 was traned in Hombu Dojo and never, any time we trained “ura”

[…] Click here to find out more. […]

Great article, very informative!

Thank you very much.

Osu

Brilliant contribution, thank you! I will direct anyone interested in kata to this article, it clarifies so many issues.

can someone please tell me what is Oyama karate Kihon kata and the history of these katas, are they Kyokushin?

Not to forgot that M Oyama also train Whith General Choi hong hee , founder TKD ,

I am a 3 Dan in traditonal old school kyokuskinkai , and 2 dan in TKD , many similare teqniques ,

Thanks ,awsome ,tiger schulmannwas a student under mas oyama in kyokushin.love the history ,who trained me….

Wow, so many deep information ..

Thank you for sharing this article and who wrote it ..

Oss

I will like to be your member.

I have studied Kyokushin back in the day..reached Shodan. Under Sensei Lee Getty…then I trained in Shotolan reached Hachidan. then I trained in Kempo reached Kudan. after the years past. I founded the system called Shoju-Kempo ryu which is three systems combined together. Shotokan, Jujitsu, Kempo. You can find me the book Who’s Who in the Martial Arts. Professor Larry Martin.

This was great. So many things I never thought about. I do believe that there is to much emphasis on doing the stance, turn technique correct and not enough time spent on learning why we do what we do.