In the original article I attempted to introduce the origins of Taikiken in Kyokushin. For this part, I am posting an excerpt from the book, “The Essence of Kung-fu Taiki-KEN”, by the founder, Kenichi Sawai. Kenichi Sawai was a long time friend and teacher of Mas Oyama, and introduced Sosai to Taikiken. In this excerpt he talk about his introduction into yiquan. I hope you enjoy and it peeks your interest in this forgotten part of Kyokushin, but still practiced by some, including Shihan Hajemi Kazumi and Kancho Hatsuo Royama.

History of Taiki-ken, by Kenichi Sawai

Taiki-ken, the subject of this book, has developed from Hsing-i-ch’üan (Xing Yi Quan). Chinese hand-to-hand combat schools may be divided into two major categories: the inner group and the outer group. Hsing-i-ch’üan (Xing Yi Quan), T’ai-chi-ch’üan (Taijiquan), and Pa-kua-ch’üan (Baguazhang) belong to the inner group, whereas Shao-lin-ch’üan belongs to the outer group. Though there are problems inherent in the very act of making such a division, an understanding of the difference between the inner and outer groups is of the greatest importance to an understanding of Chinese hand-to-hand combat in particular and of all the martial arts in general.

In the schools of the outer group, practice is devoted to training the muscles of the body and to mastering technical skills. On the surface, this method seems to produce greater strength. Since the techniques themselves can be understood on the basis of no more than visual observation, they are comparatively easy to learn. The schools of the inner group, however, emphasize spiritual development and training. They develop progress from spiritual cultivation to physical activity. In general, the inner schools give a softer impression than the outer schools; but training in them requires a long time, and mastery of them is difficult to attain.

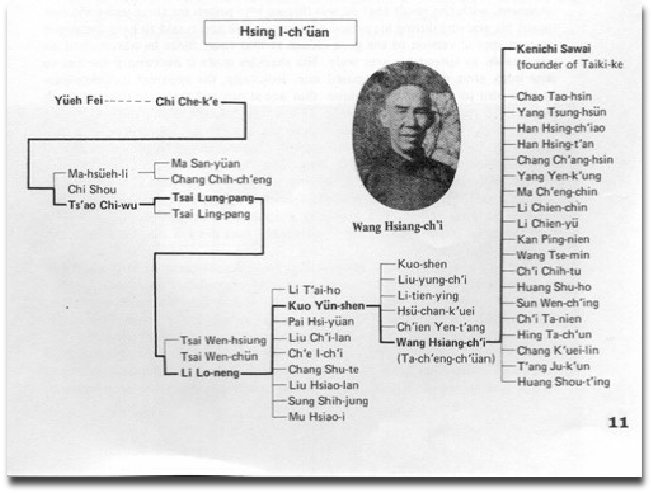

It is generally said that Hsing-i-ch’üan was originated by a man named Yueh Fei, but there is nothing to prove this attribution. Later a man named Li Lo-neng of Hupei Province became very famous in Hsing-i-ch’üan combat. His disciple Kuo Yun-shen became still more famous for his overwhelming power. It is said that of all the men who participated in combat bouts with him only two escaped deaths. These two were his own disciple Ch’e I-ch’i and Tung Hai-chuan of the Pa-kua-ch’üan School. Kuo Yun-shen himself killed so many martial-arts specialists from various countries that he was imprisoned for three years.

While in prison he perfected the mystical technique that is known as the Demon Hand. With the appearance of Kuo Yun-shen, the fame of hsing-i-ch’üan spread throughout China. Other outstanding specialists in this tradition include Kuo Shen, Li Tien-ying, and Wang Hsiang-ch’i. Wang was the founder of Ta-ch’eng-ch’üan in this capacity he is known as Wang Yü-seng and was my own teacher. Sun Lu-t’ang, a disciple of Li Tien-ying, saw the elements shared in common by Hsing-i-ch’üan, Pa-kua-ch’üan, and T’ai-chi-ch’üan and developed a school consolidating all of them. Lu Chi-lan, who was a student at the same time as Kuo Yun-shen, accepted the teachings of Hsing-i-ch’üan in their pure form, passed them on to his disciples Li Ts’un-i, who in turn passed them on to his disciple Hsiang Yunhsing. In this way, a conservative school was established. Three strains have developed since the time of Kuo Yün-shen within the larger Hsing-i-ch’üan school: the conservative strain of Li Ts’un-i, the Hsin-I branch of the Ta-ch’eng-ch’üan of Wang Hsiang-ch’i, and the conservative strain of Sun Lut’ang. In a two-volume work entitled – Hsing-i-ch’üan, Sun Lu-t’ang has written in detail about Wang Hsiang-ch’i. The Hsin-i group, as I have indicated, is another name for the Ta-ch’eng-ch’üan, which is a subgroup founded within Hsing-I-ch’üan by Wan Hsiang-ch’i. I can explain the origin of the name Ta-ch’eng in the following way. Wang Hsiang-ch’i believed that the power of the mystical techniques of Kuo Yun-shen was to be found in a force called ki in Japanese (the word is pronounced ch’i in Chinese.)

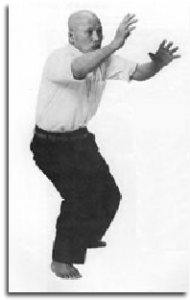

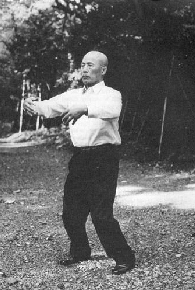

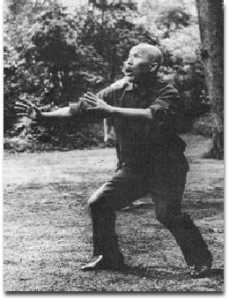

He also believed that, unless a person learns to control and use ki, he cannot master any of the combat techniques. In order to develop the needed mastery, Wang concentrated on standing Zen meditation. In combat with another person, the man who can control ki and manifest it to the extent reuired has attained and understanding of the kenpo of Wan Hsiang-ch’i. Such attainment is called ta-ch’eng in Chinese (the same characters are read tai-sei in Japanese). This is the reason for using ta-ch’eng in the name Ta-ch’eng-ch’üan. I met Wang Hsiang-ch’i while I was working in China. He was a small man with a most ducklike walk. But he was extremely difficult to study with. When people came wanting to learn his system, he ignored them. They had no recourse but to observe his actions and, practicing together, try to imitate his techniques. Fortunately, being a foreigner, I was able to ask questions and do things that would have been considered very rude in another Chinese.

Since at the time I was a fifth dan in Judo, I had a degree of confidence in my abilities in combat techniques. When I had my first opportunity to try myself in a match with Wang, I gripped his right hand and tried to use a technique. But at once found myself being hurled through the air. I saw the uselessness of surprise and sudden attacks with this man. Next I tried grappling. I gripped his left hand and his right lapel and tried the techniques I knew, thinking that, if the first attacks failed, I would be able to move into a grappling technique when we fell. But the moment we came together, Wang instantaneously gained complete control of my hand and thrust it out and away from himself. No matter how many times I tried to get the better of him, the results were always the same. Each time I was thrown, he tapped me lightly on my chest just over my heart. When he did this, I experienced a strange and frightening pain that was like a heart tremor.

Still I did not give up. I requested that he pit himself against me in fencing. We used sticks in place of swords; and, even though the stick he used was short, he successfully parried all my attacks and prevented my making a single point. At the end of the match he said quietly, ‘The sword- or the staff- both are extensions of the hand.’ This experience robbed me of all confidence in my own abilities. My outlook, I thought, would be very dark indeed, unless I managed to obtain instruction from Wang Hsiang-ch’i. I did succeed in studying with him; and, acting on his advice, I instituted a daily course in Zen training. Gradually I began to feel as if I had gained a little bit of the expansive Chinese martial spirit. Later, after I had mastered Ta-ch’eng-ch’üan, I founded another branch of combat training, which I call Taiki-ken. (This is the Japanese reading of T’ai-ch’i-chuan. Since I am Japanese, I shall use the Japanese reading throughout this text.) As a foreigner, I was able to gain the permission of Wang Hsiang-ch’i to substitute characters in the name of his school of kenpo to form the name for my own school. And this is the way the name Taiki-ken came into being. I am proud to be part of a martial-arts tradition as long as that of Ta-ch’eng-ch’üan. Whenever I think of the past, I see Wang Hsiang-ch’i and hear him saying, ‘No matter if you hear ki explained a thousand time, you will never understand it on the basis of explanations alone. It is something that you must master on your own strength.’

My course of training in China was arduous and long- eleven years and eight months. When World War II ended, I returned to Japan. Once in my training hall in Japan, I was suddenly surprised to feel something that I suspected might be the ki of which Wang Hsiang-ch’i used to speak. This surprise was the rebeginning of Taiki-ken, to which I intend to devote myself for the rest of my life.

I should like to add more details to the explanation I have already given of Hsing-i-ch’üan in the discus- sion of the history of Taiki-ken. Hsing-i ch’üan (also known as Ksin-i-ch’üan) is said to have been origi- nated in the Sung period (tenth to thirteenth century) in China by a man named Yueh-fai, though t ere is nothing to prove this. From the late Ming to the early Ch’ing period (about the second half of the seven- teenth century), in province of Shansi, there ap- peared a great expert in the use of the lance; his name was Chi Chi-ho. By about this time, the basic nature of Hsing-i-ch’üan was already determined. The tradition was inherited and carried on by Ts’ao Chi-wu and Ma Hsueh-li. In the Ch’ing period (which lasted from 1644 until 1912), Tsai Neng-pang and Tsai Ling-pang became disciples of Ts’ao Chi-wu.

Lin Neng-jan , who lived in Hopei province, heard rumours about Tsai Neng-pang and decided to study with him. In his late forties, Li Neng-jan became so skillful and powerful that he was called ‘divine fist.’ His skill and speed were so great that opponents never had a chance to come close to him. After he returned from the place in which he had been studying to his home province of Hopei, he concentrated on training disciples, with the consequence that Hopei Hsing-i-ch’üan became famous throughout China. He had many disciples, but among them Kuo Yun-shen was the most famous. He was said to have no worthy opponents in the whole nation. Kuo Yun-shen was especially noted for his skill in a technique called the peng-ch’üan, with which he was able to down almost all corners. In one bout, he employed this technique and killed his opponent, with the result that he was thrown into prison for three years. He continued his training during his period of incarceration and is said to have developed his own special version of the peng-ch’üan at that time. Since he was chained, he was unable to spread his arm wide. His shackles made it necessary for him to raise both arms whenever he raised one. Ironically, the apparent inconvenience enabled him to develop a technique that was at one and the same time an attack and a steel-wall defence. He learned to maintain a sensible interval between his own body and his opponent and to counter attacks and immediately initiate attacks. It took him the full three years of his term in jail to perfect this technique. Although he was not a big man, Kuo Yun-shen was very strong. Once a disciple of another school of martial arts asked Kuo to engage in a match with him. Kuo complied with the man’s wish and immediately sent him flying with one blow of his peng-ch’üan. The man rose and asked for another bout. Once again Kuo did as he was requested, but this time the man did not rise, because one of his ribs was broken.

The study of Hsing-i-ch’üan involves first basic development of ki through Zen then the study of the Chinese cosmic, philosophy called T’ai-chi-hs5eh, which originated as a system for divination and reached full development during the Sung period. The physical aspects of training involve five techniques called the Hsing-i-wu-hsing-ch’üan: the p’i-ch’üan (splitting fist), peng-ch’üan (crushing fist), tsuan-ch’üan (piercing fist), p’ao-ch’üan (roasting fist), and the Kuo-ch’üan (united fists) plus a fifth that is an advanced application technique called the lien-huan-ch’üan (connected-circle fist). As a person practices using these techniques in training sessions and bouts with opponents, he gradually learns which suits him best.

Hsing-i-ch’üan is further characterized by forms (hsing in Chinese and kata in Japanese) based on the instinctive motions of twelve actual and mythical animals: dragon, tiger, monkey, horse, turtle, cock, eagle, swallow, snake, phoenix, hawk, and bear.The very name Hsing-i-ch’üan means that it is the ability to use these motions without conscious consideration that gives the system its meaning. The practitioner of Hsing-i-ch’üan must use the forms automatically and without reference to his conscious will. The point that sets Hsing-i-ch’üan most clearly apart from other martial arts is related to this theory, for in Hsing-i-ch’üan training, no matter how thoroughly a person may have mastered the techniques, if he is unenlightened about the basic meaning of the forms, his efforts are wasted. People striving for progress in the martial arts must be aware of this point and must keep it in mind throughout their daily practice. Relations between opponents in Hsing-i-ch’üan are especially distinctive in three respects.

First, since there is no way of knowing what kind of attack the opponent will try, Hsing-i-ch’üan does-not prescribe such things as maintaining fixed distances and employing kicking techniques. Instead, the individual must always move toward his opponent and counter his moves as he attacks. Second, since defense must always be perfect, in Hsing-i-ch’üan, one arm is always used for defence purposes (it may be either the mukae-te or the harai-te method; see p. 34 and 60). Third, there is no strategy, and no restraints are used in Hsing-i-ch’üan matches. Since the individual’s body must move naturally, easily, and rapidly in conformity with the opponent’s movements, there is no time for mental strategy. Nor is there any need for restraining the opponent with one hand while kicking. At all times, maintaining a perfect defense, the person must conform to the motions of his opponent. This, as I have said, leaves no time for mental strategy.

Osu,

Interesting post and article – please see this was from one of the Kyokushin quaterly magazines published during Mas Oyama’s time.

this was from one of the Kyokushin quaterly magazines published during Mas Oyama’s time.

Does give a different perspective.

The story of sensei Sawai meeting with master Wang is also discussed in this movie: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXkeaDZcMtY [01:30]. It is very interesting that he said that the basic training is like punishment at school [08:45]): you just stand still as long as possible to create the iron gate by developing the Ki. Because you don’t know how the proces of developing the Ki will actually happens, it really feels like punishment: “Just do it”. Even the master could not tell (“I can try to explain it 1000 times but you will still don’t grasp this phenomenon with words”). In analogy, no… Read more »

Osu Scott, thank you for starting part 2 of the Taikiken subject, I’ve enjoyed reading it. I’ve done a Taikiken workshop with sensei Ron Nansink last year, and I could borrow this book for a day or two during the workshop. I wonder if there is a more detailled information available about the exact relationship between sensei Sawai en sosai Oyama. In Wikipedia for example, and also in his books, sosai didn’t mention his study in Taikiken, as far as I know. That is maybe the reason why there is a question whether Taikiken and Kyokushin were already integrated as… Read more »