|

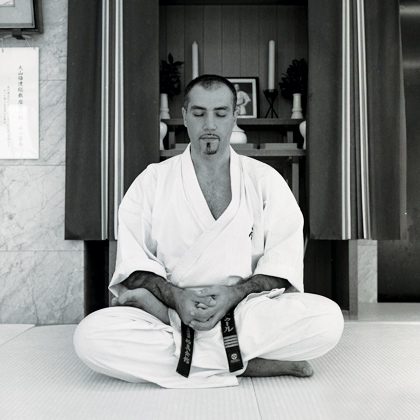

The 100-man kumite is not for everyone. In fact, less than 20 people in the world have ever partaken in this brutal test of karate skill, endurance and, most of all, spirit. But Sensei Artur Hovhannisyan knew from his very early days in karate that this would be the ultimate test in his search for his ‘ultimate truth’ — the way of Kyokushin. In this exclusive interview, the Armenian-born former karate champion talks about his 100-man kumite experience, his career as a full-contact fighter and how becoming a head trainer at IKO honbu in Japan has changed his life. |

|||

Sensei Artur, why and how did you first come to get involved in Kyokushin karate? In 1990, by the recommendation of a friend, I was allowed to attend training in the Sensei K. Manukyan dojo (branch chief of Armenia). This was after the lifting of the ban on ‘the practice of karate’ in the USSR; therefore, every child wanted to do karate. It was a boom time for karate. Is it now a popular art in your homeland of Armenia? First, Kyokushin was not very popular, but thanks to the work of the Armenian Federation, year by year Kyokushin became better known to people and is now strong. Is the Armenian way of training karate different from how things are done in Japan? No difference at all. Almost every year Japanese instructors conduct training camps in Armenia. Also, Armenian instructors come to Japan to study karate, as it is taught in the Japanese honbu [headquarters]. How long have you been living in Japan and how have you adapted culturally to living there? It has been eight years since I moved to Tokyo. The first two years were difficult. I did not speak the Japanese language, I did not properly understand Japanese customs and I did not understand the mentality of the Japanese people.

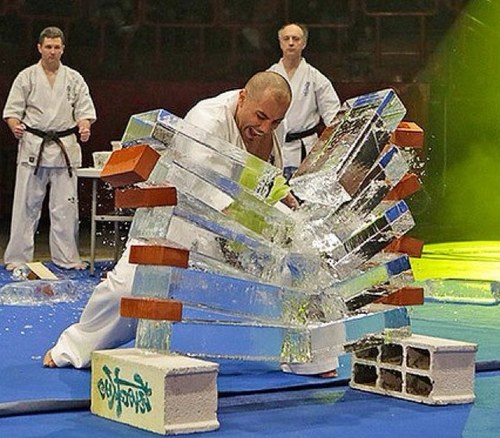

For example, it was at least very strange for me that Japanese does not use word ‘yes’ or ‘no’. When I was asking students after my explanation, “Do you understand everything?”, they just answered “Daijubu desu”, which means ‘everything is fine’ or ‘I am okay’. But Honbu accepted me as a member of the family, and all the guys helped me to adapt to my new place of residence. Across several of the major Kyokushin organisations, it seems the Europeans and South American fighters are starting to dominate, even over the Japanese. Why do you think this is? What is different about the European way of training or fighting that’s working so well? Or what are the Japanese perhaps not doing? I think this is quite simple. Life is like ‘sinusoid’ –— sometimes we go up, and sometimes we go down — like yin and yang. [Editor’s note: the sine wave or sinusoid is a mathematical curve that describes a smooth, repetitive oscillation]. As a European, it is unusual — and a particular honour — to be given the job of a head instructor at a Japanese honbu dojo. Do you think you have been enlisted to teach at Honbu in part to bring some of the European Kyokushin methodology back to the home of the art? Yes, it is unusual and yes, it is a great honour for me and for all Armenian and European Federations of Kyokushinkai. However, I can only guess the main reason for my invitation to the honbu. An ability to learn, big potential and the ability to transfer karate tradition to the next generation — perhaps this is what Kancho Matsui saw in me eight years ago. What has this appointment meant for you in terms of personal satisfaction, and your development in Kyokushin? For me, it is above all an opportunity to train with the great masters of karate Kyokushinkai; to learn [karate] from them, as well as the philosophies of martial arts and Japanese culture. What would you consider to be your greatest achievements and toughest challenges in your karate career so far? Without any doubt, the 100-man kumite was the most difficult challenge of my karate career. Harking back to that 100-man kumite in 2009, it’s said that you went out with a particularly hard approach rather than minimising punishment and counter-fighting, as others have done, in order to survive the 100 rounds. Was there any reason for taking this ‘harder road’ — were you out to prove a point, to yourself or others? Or do you not think you approached it any differently to other fighters? Everyone who has done a 100-man kumite chooses his own path, and it is different from the others. I went through mine. How did your training for the 100-man kumite compare to your preparation for major tournaments? Did you do anything differently, and can you describe your regimen leading up to it? The entire process of my training was under the control of Sensei Ryu Narushima. He adjusted the training schedule, the amount and time of the exercise. Of course it was different from the usual preparation for a tournament, because I had to fight for at least three hours. So my daily training sessions were also three-to-four hours, sometimes even five-to-six hours. One of the exercises that Sensei Narushima made me do was one hour non-stop of roppon geri [Editor’s note: this is a variation on Kyokushin’s well-known gohon geri five-step kicking combination, with one additional kick in each combination. Those practitioners who have perhaps done gohon geri for 10 or sominutes will understand the extreme demands of one hour of roppon geri!] Why did you want to do the 100-man kumite? Why was it important to you? It’s a really difficult question. When I first started karate, I watched the video of Kancho Matsui completing the 100-man kumite. I was only a White-belt, but something in me was born: the idea to make the 100-man kumite. From that moment I wanted to make the 100-man kumite, but why, I do not know. Can you describe your mental state going into the kumite? What it was like towards the end, and after you’d accomplished it? Determination to do it and 100 per cent concentration. After my last fight (the 100th fight was with Shihan Francisco Filho), there was complete absence of thoughts. A little later, all the feelings came rushing along at once: gratitude, joy, sadness, pain, satisfaction, pride, respect, patience, compassion, regret… What was the toughest moment for you during the whole event? Fights starting at about 73 and going through to 90. Those fights I cannot remember. What was the final toll on your body — what injuries did you sustain and how long did it take you to recover? My whole body was bruised and swollen. [I suffered]dehydration and loss of more than five kilos of weight. My every movement caused me pain. I could barely move. Sensei Joji Hibino took me to the hospital, where I was checked for broken bones, internal bleeding and other serious injuries — thank God, everything was fine. I was put on an intravenous drip and after a while they let me go home.

How do you prepare mentally immediately before an event like that? If I remember well, I did not do anything special. I tried to stay focused, but not to think much about the fight. Who has been your toughest opponent in your full-contact career? Alejandro Navarro — not physically, but mentally! We are like brothers, and to be able to fight with him I had to fight with myself first. And your toughest fight outside of the 100-man kumite? For the reason I mention above, fighting with Alejandro at the 38th All Japan Tournament in 2006. Who has had the greatest influence on your journey? Kancho Shokei Matsui. We understand that this has been your first visit to Australia. What is it that brought you to Australia? By invitation of branch-chief Shihan Trevor Tockar I visited Australia. Shihan Tockar’s goal is the same as mine as a representative of the Japanese Honbu. It is to share experiences, exchange new information and work on small possible mistakes. Due to the diligence and working capacity of the students, we conducted a successful seminar and were able to work on all aspects of karate Kyokushinkai training. Did you enjoy your stay in Australia, and do you intend to come back at any time in the future? Very, very much! And of course I would like to come back to Australia to train with my ‘Australian Kyokushin family’. We understand that Sensei Garry O’Neill was in Sydney for the seminars and grading conducted by you at Shihan Tockar’s dojo at North Bondi. Did you enjoy working with Sensei Garry and do you think that his unique style of fighting would still be effective in today’s tournaments? Sensei Garry has always been an example for me. And, of course, for me it was an honour to work with him, to share experiences and to learn from him. His perfect technique, accessibility to everyone, clear explanations and great attitude to karate can motivate anyone, from White-belt to Black-belt. What are your impressions of what you have seen of Kyokushin karate in Australia? Only one word: Family. Do you have any particular message for karateka in Australia? Keep training hard. Set goals and achieve them.

Originally posted by Blitz Australasian Martial Arts Magazine |